-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

On August 12, 1918, Edgar B. Speer, a BOI (Bureau of Investigation)[1] special agent in the Pittsburgh office, sent to the New York office a telegram reproducing a notice from a certain Tremble, probably one of their informants or agents, who recommended his colleagues verify the following information through a search of the subject’s place:

“Tremble advises from confidential sources [that] Kahlil Gibran, a Syrian alien with [an] art studio [on the] third floor, West 10 Street, has in his possession considerable mass peace propaganda—literature of Bolshevik type. [Tremble] suggests [a] search of [Gibran’s] effects may prove valuable.”

Such a circumstance, apparently unexplainable, needs to be framed into the historical context of the time to be understood. From 1917 in the USA, with the events of the country’s entry into World War I and the October Revolution in Russia, an anti-Communist alarm began to spread within the American government circles. The so-called First Red Scare, which lasted until 1920, was the name of a campaign against leftist radicalism and, during the war years, neutralist and pacifist dissent. It was, to quote the words of Murray Burton Levin (1927-1999), “a nationwide anti-radical hysteria provoked by a mounting fear and anxiety that a Bolshevik revolution in America was imminent – a revolution that would change Church, home, marriage, civility, and the American way of Life.”

News media exacerbated such fears, channeling them into anti-foreign sentiment: immigrants, most of whom were poor, were seen by many WASP Americans as potential or actual anarchist, socialist, Soviet sympathizer, capable of unpredictable subversive and violent acts as possible solutions to their poverty. In addition, laws such as the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 criminalized many forms of speech, any disloyal language, whether printed or spoken, that might cast the US government or its war effort in a negative light.

Was Gibran a Socialist? When on May 30, 1911, he met and made a drawing of Charles Edward Russell (1860-1941), member of the Socialist Party of America and founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in a letter to Mary Haskell, he expressed all his admiration for the man: “I made a drawing of a truly big man whom you admire very, very much – Mr. Charles Russel. It was a great joy to draw his remarkable face and to talk with him about art in general and about the eternal question of the Near East.”[3] Mary was a friend of some of the leading socialists of the day, notably William English Walling (1877-1936), a social reformer, Russian historian, and another founder of the NAACP, who was the brother-in-law of her sister Frederika Christina Haskell (1880-1973). It was Mary who, in 1913, lent Gibran Walling’s book The Larger Aspects of Socialism,[4] which he enjoyed:

“I, too, have been reading a good deal about Socialism. To me, it is the most interesting human movement in modern times. That does not mean that I agree with all of its details. It is a mighty thing, and I believe it will go through many changes before it becomes a form of government.”[5]

Like Mary, Gibran also had among his acquaintances many personalities more or less directly connected to New York Socialist or Communist circles, such as: Charlotte Teller (1876-1953),[6] Orrick Johns (1887-1946),[7] Joseph Gollomb (1881-1950),[8] John Reed (1887-1920),[9] Rose Pastor Stokes (1879-1933),[10] Percy Stickney Grant (1860-1927)[11] and Randolph Bourne (1886-1918).[12] Does that make Gibran a Socialist? Probably not, although, as we have seen, he looked at that ideology with sincere respect and curiosity, as he also did with the facts of 1917 in Russia:

“The great war is beginning to reveal its real significance. The change in Russia is only a start – other countries will follow. I believe that within a short time, say twenty-five years, the consciousness of the races will create governments for the races. The old self of the human race is dying fast – the new self is rising like a young giant. Germany and Austria see their future – and those who are governing Austria and Germany are full of fear. The gates of Heaven are open now, and there is no power on Earth to close them. The spirit of yesterday is no more, and the voice of yesterday is only an echo. Tomorrow will have its own spirit and its own voice. And the spirit of tomorrow is righteousness and the voice of tomorrow righteousness. It is all so wonderful, Mary, and I am glad you and I are there to see it changing. And you know, Mary, that nothing happens to the human though individuals may not be conscious of what is happening to them at all. Life has its seasons. Now the breath of Spring is in the air, and all the Czars and all the Kaisers of all the worlds cannot make time walk backward.”[13]

Years after, on February 8, 1921, Gibran talked this way with Mary about Christ: “Jesus had two leading conceptions: the Kingdom of Heaven, and a piercingly constructive critical consciousness. In this day, he would be called Bolshevik and Socialist.” On July 19, 1921, he told her:

“The English have always loved the Turks. If it hadn’t been for the English, the Turk would have been driven out of Europe by the Russians, and the people of the Near East would have been free, or have been swallowed up by Russia. Better Russia than Turkey, for Russia is young and full of creative power.”[14]

Does Gibran’s admiration for Russia – its spirit, culture, literature and art – which existed even before the October Revolution make him a Bolshevik activist? Surely not, so a further question we must ask should be: was he a pacifist? Before answering, we cannot and must not forget his commitment to the Syrian cause, as he wrote in a letter to Mary dated April 20, 1917:

“I am downtown working for Syria. Since the day America made a common cause with the Allied Governments, the Syrians and the Lebanese in this country have decided to join the French Army which is almost ready to enter Syria. With the help of some Syrians in this city, I have been able to organize a ‘Syrian-Mount Lebanon Volunteer Committee.’ I had to do it, Mary. The moral side of this movement is what the French Government sees and cares for.”[15]

However, he was well aware that his post of secretary of English correspondence in the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Volunteer Committee, advising Syrian residents in the United States on how to join the French army involved in the war, was in sharp contrast with his role in the board of the literary monthly “The Seven Arts”. The magazine, founded in 1916 in New York by James Oppenheim (1882-1932),[16] by the summer of 1917, became a passionate forum with editorials condemning the war written by Oppenheim himself, along with authors such as John Reed and Randolph Bourne. Even before the monthly was launched, Gibran knew that his association with a pacifist like Oppenheim would raise concerns among his Syrian colleagues on the Committee, yet he continued actively supporting him. On July 23, 1916, he told Mary Haskell: “He likes the things I do – and I like his ideas… He wants to publish all I’ve written in English… And some of the Syrians are angry because I have given him my name.”[17] About a year after, caught in a crisis of conscience, he tried to justify his ambivalent position when he saw Mary on July 27, 1917:

“You know I like Oppenheim – though I feel so oppositely to him about what to do in this war… I’m anti-war – but for that very reason, I use this war. It is my weapon. I’m for justice – and so I make use of this great injustice… And Oppenheim knows how I feel. He’s come to me – you know he always comes to talk things over – and I’ve told him. I don’t want to hurt the magazine, and they want to keep my name. I can’t, somehow, hurt them – so I think perhaps it is better to let things drift. My Syrian friends don’t like it – and many of them haven’t understood my still being on the Board since the magazine has been printing its recent editorials.”[18]

By October, Gibran’s dilemma over his involvement with “The Seven Arts” was solved for him, when the magazine, in severe financial problems, had to close. On November 10, he confessed to Mary that he was even thinking of leaving for the front to set a good example: “If I enlist, others also will enlist.”[19] Among the fellow Syrians of his inner circle, Mikhail Naimy (Mīḫā’īl Yūsuf Nu‘aymah, 1889-1988) was the only one to leave: in June 1918, he was sent to the Franco-German frontier in the Faubourg.[20]

As for Gibran’s countrymen resident in New York, some of them, like him, were Maronites, and some were Greek Orthodox. Many of the latter had studied at the Russian missionary schools in Palestine and Syria – like Naseeb Arida (Nasīb ‘Arīḍah, 1888-1946), editor of “al-Funūn”, and the brothers Abdulmassih Abdo Haddad (ʻAbd al-Masīḥ ʻAbduh Ḥaddād, 1890-1963) and Nudra Abdo Haddad (Nadrah ʻAbduh Ḥaddād, 1881-1950), editors of the Arab-American magazine “al-Sā’iḥ” (or “As-Sayeh”, ‘The Tourist’ or, ‘The Traveler’) –, and even in the Czarist Empire, as is the case with Naimy, who, between 1906 and 1911, attended the Theological Seminary in Poltava, in present-day Ukraine. In the USA, from 1916 until the outbreak of the Russian Revolution, Naimy worked as the assistant secretary for the Russian Consulate in Seattle, Washington, as a typist in the office of the Russian Commercial Fleet in New York, and then as a secretary to the Russian Inspector at the “Bethlehem Steel Co.” in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Arida also was chosen to study a year in Russia while at the Russian Teacher’s Training College in Nazareth, but he missed the opportunity to go due to the Russo-Japanese war (1904-1905). They were all fluent in the Russian language.

As for the Maronite Ameen Rihani (Amīn Fāris al-Rīḥānī, 1876-1940), he did not have direct connection with Russia – except perhaps for his friendship with the great Arabist Ignaty Krachkovsky (1883-1951), whom he first met in Beirut in 1910 – and could not speak Russian, but Socialism undoubtedly had a great influence on him and his thought,[21] and the Bolshevik movement would even become the subject of a book he wrote between 1919 and 1920.[22]

For Gibran the artist and the writer, the months between the autumn of 1917 and the summer of 1918 were particularly intense, profitable and successful. Forty of his paintings and drawings were exhibited at the Knoedler Gallery. He began his collaboration with the Poetry Society of America and completed the writing of two new books: his first work in English, The Madman, which would be published in October 1918,[23] and a long poem in Arabic, al-Mawākib (‘The Processions’), which would come out only in March 1919 (a paper shortage delayed it in press).[24] In the same period, he also dedicated himself to the composition of some parts of what was to become his undisputed masterpiece, The Prophet.[25]

Speer’s telegram was sent from Pittsburgh, more than 600 kilometers from New York, where Gibran resided. Had he something to do with that far city? In the spring of 1918, Gibran accepted an invitation to come and stay at a retreat at Boston writer and poet Marie Garland’s Bay End Farm in Buzzards Bay, Cape Cod, an estate in the countryside of Massachusetts. Marie Tudor Garland (1870-1949), an ardent feminist, in the early 20th century, commissioned a number of prefab cottages to be delivered and erected on her property to offer many artists and authors a sanctuary to relax and work whilst enjoying her hospitality – regular visitors, among others, were painter Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), cartoonist and illustrator Rose O’Neill (1874-1944), writers Witter Bynner (1881-1968) and Haniel Long (1888-1956).

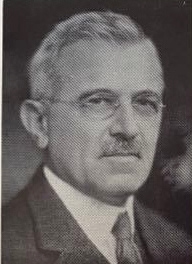

Gibran stayed at Mrs. Garland’s from April 12 to May 6. During the days he spent there, he met Franklin Felix Nicola (1860-1938), a rich Cleveland businessman and art collector who moved to Pittsburgh during the 1890s, where he had played a crucial role in the evolution of the Oakland area of the city.[26] Nicola, who was sponsoring the publication of a pamphlet advocating self-determination for the fragmented Eastern European countries, asked Gibran to be allowed to include in it his recently written poem Defeat, My Defeat. Mary Haskell saw the piece only in the last decade of May, after it was published:

“Beloved Mary. I think I told you something about Mr. Nicola of Pittsburgh, and his liking for my work – and the nice letter he wrote me about the prose-poem Defeat. He liked the poem well enough to have it printed separately in such a beautiful way (without my knowledge), thinking that it may help those who see in so-called defeat the end of active or creative life. I am sending you two copies – which I hope you will like. And if you should find any faults in the English of the poem, please let me know them. It is never too late to know mistakes.”[27]

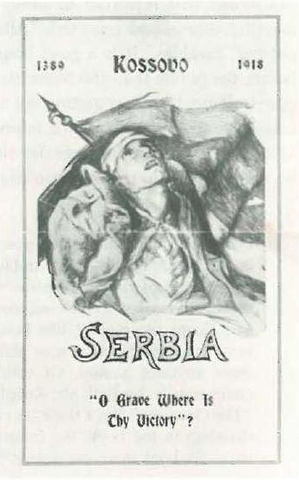

The privately printed pamphlet commemorating Serbia’s defeat by the Ottoman Empire at Kosovo field in 1389 is entitled Serbia. “O Grave Where Is Thy Victory?”. Gibran’s poem, preceded by a brief introduction, takes one unnumbered page:

The following poem has been written for Serbia by Kahlil Gibran, a Syrian poet and leader who lives in this country. It is given here as a token of all that brotherhood which unites oppressed nations in their sufferings.

Defeat, my Defeat, my solitude and my aloftness;[28] You are dearer to me than a thousand triumphs, And sweeter to my heart than all world-glory.

Defeat, my Defeat, my self-knowledge and my defiance, Through you I know that I am yet young and swift of foot, and not to be trapped by withering laurels. And in you I have found aloneness, and the joy of being shunned and scorned.

Defeat, my Defeat, my loved comrade, You shall walk with me upon the untrodden path where the faint-hearted dare not walk.

Defeat, my Defeat, my shining sword and shield, In your eyes I have read that to be enthroned is to be enslaved, and to be understood is to be leveled down, and to be grasped is but to reach one’s fullness, and like a ripe fruit to fall and be consumed.

Defeat, my Defeat, my bold companion, You shall hear my songs, and my cries, and my silence, and none but you shall speak to me of the beating of wings, And urging of seas, and of mountains that burn in the night; and you alone shall climb my steep and rocky soul.

Defeat, my Defeat, my deathless courage, You and I shall laugh together with the storm, and together we shall dig graves for all that die in us, and we shall stand in the sun with a will, and we shall be dangerous.

On May 31, Mary wrote to thank him for that unexpected gift: “I bless your dear heart for sending me Defeat. Yes indeed, I do love it. It has the winds and the voices of great inner Spaces – and a surprising something, like Summer lightnings. And there are no mistakes in the English. A few little suggestions I would make, save time, if you would like me to.”[29] But before receiving that from her, on May 29, he sent Mary another letter to tell her about a dinner with some illustrious personalities on May 26 at Mrs. Douglas Robinson’s. The hostess was the American poet, writer and lecturer Corinne Roosevelt Robinson (1861-1933), an active member of the Republican Party. She also was the younger sister of former president Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (1858-1919) and an aunt of future First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962), the wife of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945). Corinne’s parents were businessman and philanthropist Theodore Roosevelt Sr. (1831-1878) and socialite Martha Stewart Bulloch (1835-1884). Her husband was American businessman Douglas Robinson Jr. (1855-1918). Besides Gibran, the other guests at her table were: Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924), General Leonard Wood (1860-1927) and Alexander Lambert (1861-1939), director of civilian relief of the American Red Cross in France during the World War I, teacher and physician.

“Last Sunday, at Mrs. Douglas Robinson’s, I dined with Senator Lodge, General Leonard Wood and Dr. Lambert, the head Surgeon of the Red Cross. It was a remarkable evening, and we talked about the war. I was indeed very much impressed by these unusual men because each one of them is a specialist and knows a great deal about one good thing. There is something about Gen. Wood that moves one’s very depth. He is a force, much needed now, yet not used. I have read, since Sunday, that he is not to serve in France.[30] The whole affair hurts me so much that I have been tempted to write him a long letter. Dr. Lambert’s experiences in France are extremely thrilling, and he knows just how to disclose his experiences. He has the gift of words. Senator Lodge is interested in literature. He is writing a paper on The Tempest of Shakespeare!”[31]

On July 11, Gibran told Mary again about Franklin Nicola and an encounter with him that took place on July 9:

“Mr. Nicola, the rich man of Pittsburgh, came to see me two days ago – then I dined with him. He is the most fatherly man I have ever seen, about sixty years old, very simple, and has a deep, religious understanding of life, art and human beings. He told me that he is arranging, with Haniel Long, the poet, an exhibition of my pictures in Pittsburgh for next Spring. I think he will succeed. He is a man who can do anything he wants to do in Pittsburgh.”[32]

Was there a connection between Mr. Nicola – and the consequent publication of Defeat – and the BOI notice on Gibran? Who

denounced him? Almost certainly we will never know. As for the poem, when, later, the author decided to include it in The Madman and Mary volunteered to work on it, he refused her offer: “It’s all printed now, and can’t be changed. And it doesn’t matter much after all. Perhaps I oughtn’t ever to have included it in the book.”[33] Was there a particular reason for excluding that poem from the book? Another question which we will never know the answer to. Gibran left New York for Cohasset on August 10 and stayed there until August 27: “I wanted to stay here a few more days, but both the Syrian committee and Mr. Knopf seem to think that I am very much needed. […] My days here have been rather fruitful. I have added seven new processions to the original Arabic poem. But each one of the new processions calls for a new drawing. So, you see, Mary, that I am not only hard-pressed by things outside myself but also by things inside. But all is well with me, and God is most generous and kind.”

denounced him? Almost certainly we will never know. As for the poem, when, later, the author decided to include it in The Madman and Mary volunteered to work on it, he refused her offer: “It’s all printed now, and can’t be changed. And it doesn’t matter much after all. Perhaps I oughtn’t ever to have included it in the book.”[33] Was there a particular reason for excluding that poem from the book? Another question which we will never know the answer to. Gibran left New York for Cohasset on August 10 and stayed there until August 27: “I wanted to stay here a few more days, but both the Syrian committee and Mr. Knopf seem to think that I am very much needed. […] My days here have been rather fruitful. I have added seven new processions to the original Arabic poem. But each one of the new processions calls for a new drawing. So, you see, Mary, that I am not only hard-pressed by things outside myself but also by things inside. But all is well with me, and God is most generous and kind.”

He and Mary did not see each other at all that summer. They finally could meet at his studio-apartment on the last day of August.

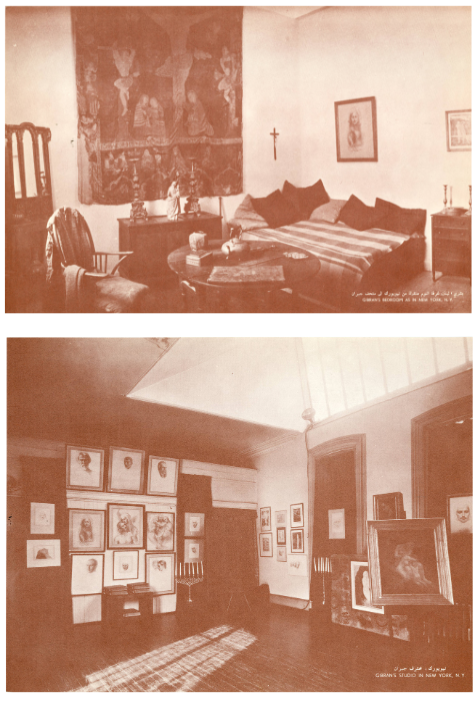

Neither could imagine what had happened right in that place only a few days earlier. On Thursday, August 15, 1918, at an undisclosed time, taking advantage of Gibran’s absence, Rayme Weston Finch, a BOI agent in the New York field office,[35] and his colleague Vladimir J. Lazovich, Special Employee, went to the Tenth Street Studio Building (also known as ‘The Studios’), situated at 51 West 10th Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues in Manhattan, New York. Constructed in 1857, it was the first modern facility designed solely to serve the needs of artists, and Gibran lived there since September 1911, after leaving the Boston apartment that he had shared with his sister Marianna (Maryānā Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, 1885-1972).

In May 1913, he moved permanently from the first to the third story, in a larger studio that he considered a refuge away from the sprawling city and that precisely for this reason he used to call ‘The Hermitage’ (al-Sawma‘ah, in Arabic). How did the story told so far end? In a rather humorous and grotesque way. In his report, Finch wrote as follows:

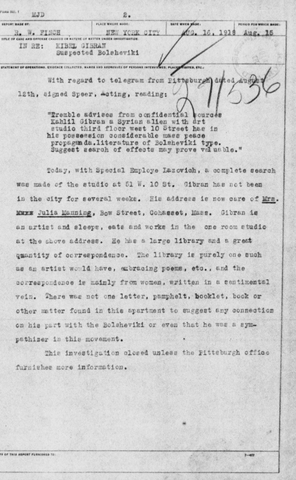

“Today, with Special Employee Lazovich, a complete search was made of the studio at 51 W. 10 St. Gibran has not been in the city for several weeks. His address is now care of Mrs. Julia Manning, Bow Street, Cohasset, Mass. Gibran is an artist and sleeps, eats and works in the one room studio at the above address. He has a large library and a great quantity of correspondence. The library is purely one such as an artist would have, embracing poems, etc., and the correspondence is mainly from women, written in a sentimental vein. There was not one letter, pamphlet, booklet, book or other matter found in this apartment to suggest any connection on his part with the Bolsheviki or even that he was a sympathizer in this movement. This investigation closed unless the Pittsburgh office furnishes more information.”

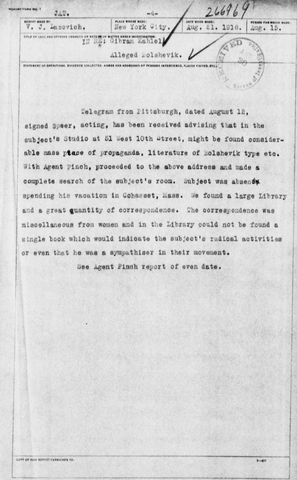

Lazovich’s report, dated August 21, 1918, confirmed the above:

“[A] Telegram from Pittsburgh, dated August 12, signed [by] Speer, acting, has been received advising that in the subject’s Studio at 51 West 10th Street, [there] might be found considerable mass peace of propaganda, literature of Bolshevik type etc.

With Agent Finch, proceeded to the above address and made a complete search of the subject’s room. Subject was absent spending his vacation in Cohasset, Mass. We found a large library and a great quantity of correspondence. The correspondence

With Agent Finch, proceeded to the above address and made a complete search of the subject’s room. Subject was absent spending his vacation in Cohasset, Mass. We found a large library and a great quantity of correspondence. The correspondence

was miscellaneous from women and in the library could not be found a single book which would indicate the subject’s radical activities or even that he was a sympathizer in their movement.”

Presumably, no further information came from the Pittsburgh office, and Gibran’s case was dismissed. What is reproduced here below is the complete and literal transcription of the two unpublished documents quoted in the present article, with all their typos, grammatical and punctuation inaccuracies, misspellings, etc. Sources are reported in the footnotes.

Report made by: R.W. Finch

Place where made: New York City

Date when made: Aug. 16. 1918

Period for which made: Aug. 15

Title of case and offense charged or nature of matter under investigation:

IN RE: KIBEL GIBRAN[36] – Suspected Bolsheviki

Statement of operations, evidence collected, names and addresses of persons interviewed, places visited, etc.:

With regard to telegram from Pittsburgh dated August 21st, signed Speer, Acting, reading:

“Tremble advises from confidential sources Kahlil Gibran a Syrian alien with art studio third floor west 10 Street has in his possession considerable mass peace propaganda.literature of Bolsheviki type. Suggest search of effects may prove valuable.”

Today, with Special Employee Lazovich, a complete search was made of the studio at 51 W. 10 St. Gibran has not been in the city for several weeks. His address is now care of Mrs. Julia Manning, Bow Street, Cohasset, Mass. Gibran is an artist and sleeps, eats and works in the one room studio at the above address. He has a large library and a great quantity of correspondence. The library is purely one such as an artist would have, embracing poems, etc., and the correspondence is mainly from women, written in a sentimental vein. There was not one letter, pamphelt, booklet, book or other matter found in this apartment to suggest any connection on his part with the Bolsheviki or even that he was a sympathizer in this movement.

This investigation closed unless the Pittsburgh office furnishes more information.[37]

***

Report made by: V.J. Lazovich.

Place where made: New York City.

Date when made: Aug. 21. 1918.

Period for which made: Aug. 15.

Title of case and offense charged or nature of matter under investigation:

IN RE: Gibran Kahlel – Alleged Bolshevik.

Statement of operations, evidence collected, names and addresses of persons interviewed, places visited, etc.:

Telegram from Pittsburgh, dated August 12, signed Speer, acting, has been received advising that in the subject’s Studio at 51 West 10th Street, might be found considerable mass peace of propaganda, literature of Bolshevik type etc.

With Agent Finch, proceeded to the above address and made a complete search of the subject’s room. Subject was absent spending his vacation in Cohasset, Mass. We found a large Library and a great quantity of correspondence. The correspondence was miscellaneous from women and in the Library could not be found a single book which would indicate the subject’s radical activities or even that he was a sympathiser in their movement.

See Agent Finch report of even date.[38]

* This article is based on an excerpt from the paper: F. Medici, Kahlil Gibran between the Great Famine of Mt. Lebanon and the First Red Scare in the USA. Unpublished and Secret Documents, «Mirrors of Heritage», Special Issue – Centennial of The Prophet, Lebanese American University (LAU), September 2023, pp. 176-225.

[1] Established on July 26, 1908, by American lawyer and political activist Charles Joseph Bonaparte (1851-1921), the BOI was the forerunner of the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency.

[2] Murray B. Levin, Political Hysteria in America. The Democratic Capacity for Repression, New York: Basic Books, 1971, p. 29.

[3] The Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell. Visions of Life as Expressed by the Author of “The Prophet”, arranged and edited by Annie Salem Otto, Houston: Smith & Company Compositors – Southern Printing Company, 1970, p. 77.

[4] William English Walling, The Larger Aspects of Socialism, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1913.

[5] Letter of Gibran to Mary Haskell, Nov. 4, 1913 (Otto, p. 279).

[6] Charlotte Rose Teller, later Hirsch, also using the pen name John Brangwyn, was an American writer and socialist. It was Mary Haskell who introduced Charlotte and Kahlil to each other in January 1908. In 1911 she had a brief love affair with Ameen Rihani.

[7] Orrick Glenday Johns, best known for his poetry, was active in the Communist Party of America in the 1930s and for a period an editor of the American Marxist magazine “New Masses”.

[8] Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, he made a name for himself in New York literary circles after immigrating with his family at the age of ten. When his father died shortly after their arrival, Gollomb and his siblings were raised by their staunchly socialist mother in the Lower East Side’s Jewish tenements. Though financial success as a journalist and author eventually cooled his radical fervor, Gollomb was active in the labor movement in his early years, a member of both the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). He taught advanced English classes at the socialist Rand School, where he encouraged other Russian Jewish immigrants to document their experiences. Gollomb wrote for several New York publications, including the “Evening Post”, the “Evening World”, and the “New Yorker”, as well as with the foreign bureaus of the Associated and the United Press. He also published an interview with Gibran (cf. Joseph Gollomb, An Arabian Poet in New York, “The New York Evening Post”, March 29, 1919, p. 1).

[9] John ‘Jack’ Silas Reed was an American journalist, poet, and communist activist. Reed supported the Soviet takeover of Russia, even briefly taking up arms to join the Red Guards in 1918. He co-founded the short-lived Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. When he died in Moscow, he was given a hero’s burial by the Soviet Union at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.

[10] She was an American socialist activist, writer, and feminist. In 1919, she was a founding member of the Communist Party of America.

[11] Also known as the ‘Radical Cleric’, he was an American Protestant Episcopalian clergyman and associate of Gibran’s in the circle of Greenwich Village luminaries, writers and artists. He became known for his support of Socialism and for his ‘forum’ for the expression of views on labor and living conditions. Grant lived in New York at 7 West 10th only a few doors away from Gibran at 51 West 10th.

[12] Randolph Silliman Bourne, a progressive writer, intellectual and journalist, is considered to be a spokesman for the young radicals living during World War I.

[13] Letter of Gibran to Mary Haskell, March 18, 1917 (Otto, p. 519).

[14] Beloved Prophet: The Love Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell and Her Private Journal, Edited and Arranged by Virginia Hilu, London: Quartet Books, 1973, pp. 359-360.

[15] Otto, p. 524.

[16] The associate editor was Waldo David Frank (1889-1967), and the advisory board also included Robert Frost (1874-1963), Louis Untermeyer (1885-1977), Edna Kenton (1876-1954), Van Wyck Brooks (1886-1963), David Mannes (1866-1959), and Robert Edmond Jones (1887-1954). Gibran was the only immigrant on the staff.

[17] Quoted in Jean Gibran & Kahlil Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World, New York: Interlink Books, 1991, p. 298.

[18] Ibid., pp. 304-305.

[19] Ibid., p. 305.

[20] Cf. Nadeem Naimy, The Lebanese Prophets of New York, Beirut: American University of Beirut, Beirut 1985, p. 98.

[21] Cf. Eugene Sensenig-Dabbous, Bolshevism and the Orient: Ameen Rihani and John Reed; Rebecca Gould, Ignaty Krachkovsky’s Encounters with Arabic Literary Modernity through Ameen Rihani, 1910-1922; Mikhail A. Rodianov, Ameen Rihani’s Heritage in Russia, in Ameen Rihani’s Arab-American legacy: From Romanticism to Postmodernism, Introduced by Naji B. Oueijan, Beirut: Notre Dame University Press, 2012, pp. 133-153, 325-362; Nijmeh Hajjar, The Politics and Poetics of Ameen Rihani. The Humanist Ideology of an Arab- American Intellectual and Activist, London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2010.

[22] Ameen Rihani, The Descent of Bolshevism, Boston: the Stratford Co., 1920.

[23] Kahlil Gibran, The Madman. His Parables and Poems, New York: Knopf, 1918. Gibran signed the contract with Alfred Abraham Knopf (1892-1984) on 20 June, 1918.

[24] Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, al-Mawākib, New York: Maṭbaʻat Mir’āt al-Ġarb al-Yawmiyyah, 1919.

[25] Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet, New York: Knopf, 1923.

[26] Nicola was a real estate developer (Bellefield and Schenley Farms companies), who, during the early 20th century, promoted a civic center plan for the Oakland district of Pittsburgh, as a new center for culture, art, and education.

[27] Letter of Gibran to Mary Haskell, May 21, 1918 (Otto, p. 572).

[28] The version of the poem included in The Madman, cit., entitled simply Defeat (pp. 46-48), reads: “aloofness”.

[29] Otto, p. 573.

[30] With American entry into World War I looming in early 1917, the most likely choice to lead American forces in France was Major General Frederick Funston (1865-1917). Funston died of a heart attack in February, leaving President Woodrow Wilson to choose from among the army’s six other major generals. Leonard Wood was recommended by several prominent Republicans, including Henry Cabot Lodge. Despite this support, when the U.S. entered the war in April, Wood’s prior criticism of the Wilson administration led Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (1871-1937) to recommend John J. Pershing (1860-1948), the most junior of the serving major generals and a Republican, but one who had been less vocal than Wood.

[31] Otto, pp. 572-573. As for the paper on The Tempest by William Shakespeare, cf. Edward Everett Hale, Prospero’s Island, Introduction by Henry Cabot Lodge, New York: Dramatic Museum of Columbia University, 1919.

[32] Otto, p. 586.

[33] Mary Haskell Journal, August 31, 1918 (quoted in Jean Gibran & Kahlil Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World, cit., p. 319).

[34] Letter of Gibran to Mary Haskell, August 26, 1918 (Otto, pp. 591-592).

[35] Cf. Paul Avrich, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996, p. 118: “Young, tall, heavy-set, with dark hair and mustache, Finch possessed both energy and brains”.

[36] As Gibran’s name was erroneously listed in R.L. Polk & Co.’s 1915 Trow General Directory of New York City, Embracing the Boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx, vol. 128, p. 768.

[37] Series: Old German Files, 1909-21; Case Number: 271536; Case Title: Suspected Bolsheviki; Suspect Name: Kibel Gibran; Roll Number: 686; Page: 1; FBI Case Files; Publication Title: Investigative Case Files of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922; Content Source: The National Archives; Publication Number: M1085; Collection Title: Investigative Reports of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922; Publisher: NARA (The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration); Short Description: NARA M1085. Roll: boi_german_257-850_0121

[38] Series: Old German Files, 1909-21; Case Number: 266969; Case Title: Alleged Bolshevik; Suspect Name: Gibran Kahlel; Roll Number: 681; Page: 1; FBI Case Files; Publication Title: Investigative Case Files of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922; Content Source: The National Archives; Publication Number: M1085; Collection Title: Investigative Reports of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922; Publisher: NARA; Short Description: NARA M1085; Roll: boi_german_257-850_0114