-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Francesco Medici

© Copyright Francesco Medici All Rights Reserved 2020

The first to translate a selection of Gibran’s works into Chinese was Mao Dun (Máo Dùn, 1896-1981), known by the pen name of Shen Dehong  (Shěn Déhóng), a much-famed and respected novelist, cultural critic and future Minister of Culture of the People’s Republic of China from 1949 to 1965. Between June and September 1923, he published in some literature weeklies his translations of eight prose poems from The Forerunner: “Poets,” “Knowledge and Half-Knowledge,” “Repentance,” “God’s Fool,” “Critics”, “Said a Sheet of Snow-White Paper...,” “Values,” and “Other Seas.”

(Shěn Déhóng), a much-famed and respected novelist, cultural critic and future Minister of Culture of the People’s Republic of China from 1949 to 1965. Between June and September 1923, he published in some literature weeklies his translations of eight prose poems from The Forerunner: “Poets,” “Knowledge and Half-Knowledge,” “Repentance,” “God’s Fool,” “Critics”, “Said a Sheet of Snow-White Paper...,” “Values,” and “Other Seas.”

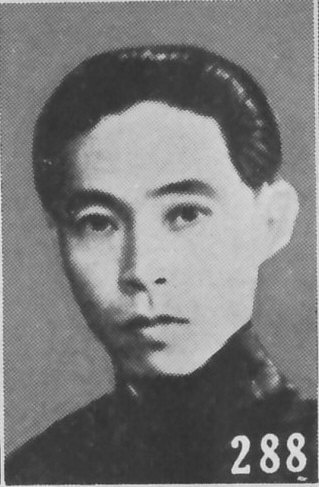

In October of that same year, the future leader of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Zhang Wentian (Zhāng Wéntiān, 1900-1976), while studying at the University of California, Berkeley, translated and published in a Chinese journal three prose poems from The Madman: “Night and the Madman”, “My Friend,” and “The New Pleasure.”

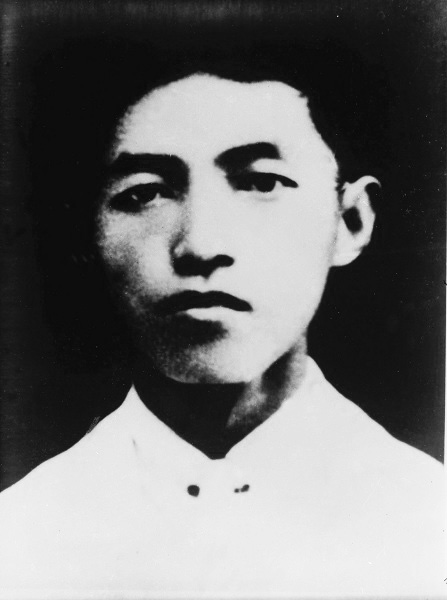

Between December 1923 and January 1924, Shen Zemin (Shěn Zémín, 1900-1933), also known by the pen name of Ming Xin (Míngxīn), Mao Dun’s younger brother and a classmate and good friend of Zhang Wentian, one of the future earliest members of the CPC, published respectively in a Chinese youth journal and in a literary weekly his own translations of three prose poems also from The Forerunner: “Poets,” “Knowledge and Half-Knowledge,” and “God’s Fool.”

younger brother and a classmate and good friend of Zhang Wentian, one of the future earliest members of the CPC, published respectively in a Chinese youth journal and in a literary weekly his own translations of three prose poems also from The Forerunner: “Poets,” “Knowledge and Half-Knowledge,” and “God’s Fool.”

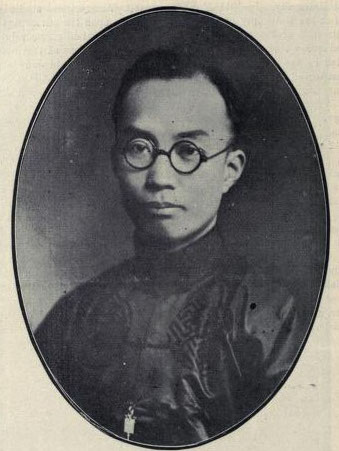

In August 1924, novelist Zhao Jingshen (Zhào Jǐngshēn, 1902-1985) published a selection of Gibran’s parables. In 1925, while serving as the dean of the School of Religion at Christian Yenching University (Peking, China), Protestant educator and church leader Liu Tingfang (Timothy Tingfang Lew, 1891-1947) began his translation of The Madman, that was published in December the following year, making it the first translation of an entire collection of Gibran’s works into Chinese. With the help of his daughter Liu Li’en, he went on to completely translate Jesus, The Son of Man and The Forerunner, that were published respectively in 1932 and 1933.

In August 1924, novelist Zhao Jingshen (Zhào Jǐngshēn, 1902-1985) published a selection of Gibran’s parables. In 1925, while serving as the dean of the School of Religion at Christian Yenching University (Peking, China), Protestant educator and church leader Liu Tingfang (Timothy Tingfang Lew, 1891-1947) began his translation of The Madman, that was published in December the following year, making it the first translation of an entire collection of Gibran’s works into Chinese. With the help of his daughter Liu Li’en, he went on to completely translate Jesus, The Son of Man and The Forerunner, that were published respectively in 1932 and 1933.

Although Liu Tingfang was the largest translator of Gibran’s works into Chinese, because of the limited circulation and distribution of the publications in which his translations appeared, he did not reach a very broad audience. It was the great writer Xie Wanying (Xiè Wǎnyíng, 1900-1999), better known by her pen name Bing Xin (Bīngxīn), who put Gibran on the map for Chinese readers through her translation of The Prophet.

In 1923, when Gibran first published The Prophet, Bing Xin, who had just graduated from the Arts Faculty of Yenching University with a B.A. in Literature, went to the United States to study at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, where she earned an M.A. in English Literature in 1926. She then came back to Yenching University to teach until 1936.

In 1923, when Gibran first published The Prophet, Bing Xin, who had just graduated from the Arts Faculty of Yenching University with a B.A. in Literature, went to the United States to study at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, where she earned an M.A. in English Literature in 1926. She then came back to Yenching University to teach until 1936.

Her acquaintance with The Prophet began when she read the work in 1927. The following spring, she invited students from her writing class to translate some parts from the book. She began to translate it herself while ill in bed in 1930 (she was affected by tuberculosis) and in the summer of 1931 – precisely when Gibran’s remains were brought from New York to his native Bcharré –, she completed the translation and published it in Shanghai with the title Xianzhi (Xiānzhī).

Her acquaintance with The Prophet began when she read the work in 1927. The following spring, she invited students from her writing class to translate some parts from the book. She began to translate it herself while ill in bed in 1930 (she was affected by tuberculosis) and in the summer of 1931 – precisely when Gibran’s remains were brought from New York to his native Bcharré –, she completed the translation and published it in Shanghai with the title Xianzhi (Xiānzhī).

Bing Xin’s long literary career was prolific and productive, with a wide range of works – prose, poetry, novels, reflections, etc. She also undertook various translation tasks, including the translation of the works of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). Once, talking about the two authors, she commented:

Tagore is a nobleman, from a good family and has been well educated since childhood. His works are full of emotions, bright voices and colorful words. The style is also more naive, more cheerful and more mysterious. Gibran is a poor man, and his work is more like the vicissitudes of an old man who is talking about the philosophy of being human, revealing a faint sorrow in the calm.

* This article is based on an excerpt from the paper “Gibran’s ‘The Prophet’ in All the Languages of the World”, 5ème Rencontre Internationale Gibran, IMA, Paris, 3 Octobre 2019, Lebanese American University–LAU, Beirut: Center for Lebanese Heritage, Lebanese American University, 2020, pp. 111-135.

Credits:

The Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland (https://gibranchair.umd.edu)

Lebanese American University (https://www.lau.edu.lb)