-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

By Eddy Choueiry

All rights reserved © copyright 2025

"It is a pity you cannot sit upon a cloud".

Sand and Foam : 1926

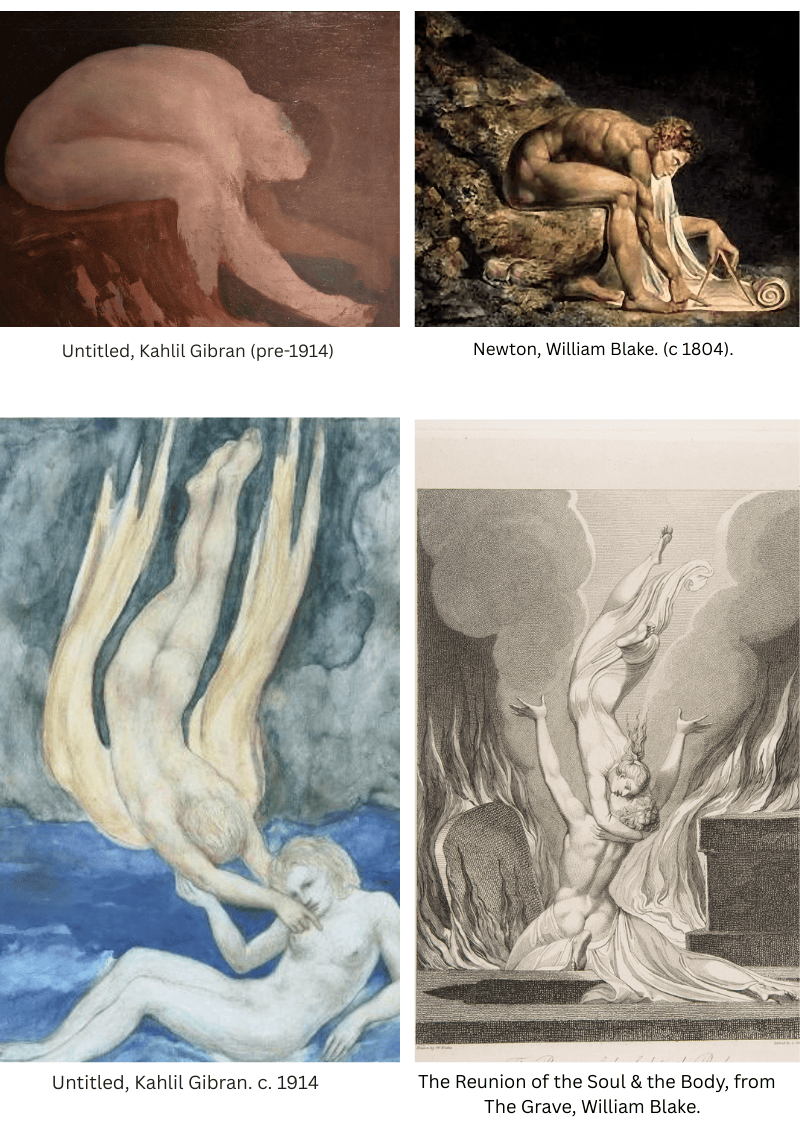

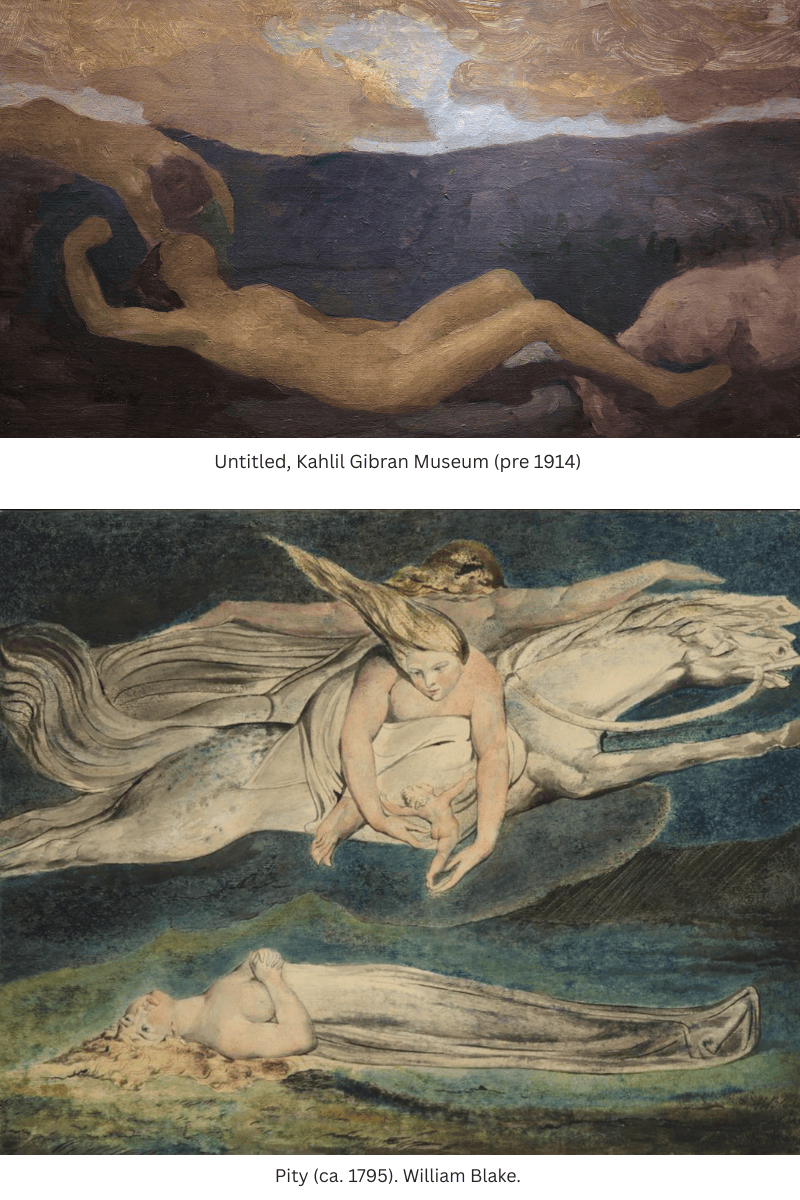

Once, I heard someone say that in culture, we could substitute Kahlil Gibran’s literature with the works of Francis Marrash, Nietzsche, or Tagore, and his paintings easily with those of J.M.W. Turner, William Blake, or Eugène Carrière. As a researcher, I traced his influences to compare his ethereal figures to Turner’s luminous atmospheres, his spiritual symbolism to Blake’s mystical visions, or his textured portraits to Carrière’s smoky haze. Yet this quest quickly revealed a deeper question: Can we identify an artist utterly untouched by others? Is Gibran a singular visionary or a brilliant synthesist? To understand his artistic evolution, we must consider the five major stages of his life:

ϕ His Lebanese Years (1883-1895): From birth to emigration.

ϕ His American Years (1895-1908): Study, painting, and meeting Mary Haskell.

ϕ His Return to Lebanon (1898-1902): To study Arabic language and literature.

ϕ His Parisian Sojourn (1908-1910): Formal art training at the Académie Julian and with Pierre Marcel-Béronneau

ϕ His Final Chapter in New York (1918-1931): Writing in English and refining his mature pictorial style.

The Style of Gibran

This essay focuses on unravelling the distinct style of Gibran’s visual art. The late Professor Wahib Keyrouz, longtime curator and protector of the Gibran Museum in Bsharri, dedicated over 37 years to this pursuit. In his book “عالم جبران الرسام” (The World of Gibran the Painter, 1982), he concludes that Gibran’s style is fundamentally introspective; the external form is merely a vessel for the internal vision and his creative process moves from the inside out. Gibran’s colours are not merely descriptive but possess an inner, cosmic dimension. Their uniqueness lies in an Eastern, almost Sufi spirituality, achieved through an ascending gradation from the dense and earthly to the weightless and transparent. This signature style emerged not in his early oil paintings (pre-1908) but later, in the watercolour and charcoal drawings that illustrate his masterpiece, The Prophet. Keyrouz describes this as a spiritual loop: an ascending movement from the earth met by a descending grace from the universal Mother to the world of Earth.

This essay focuses on unravelling the distinct style of Gibran’s visual art. The late Professor Wahib Keyrouz, longtime curator and protector of the Gibran Museum in Bsharri, dedicated over 37 years to this pursuit. In his book “عالم جبران الرسام” (The World of Gibran the Painter, 1982), he concludes that Gibran’s style is fundamentally introspective; the external form is merely a vessel for the internal vision and his creative process moves from the inside out. Gibran’s colours are not merely descriptive but possess an inner, cosmic dimension. Their uniqueness lies in an Eastern, almost Sufi spirituality, achieved through an ascending gradation from the dense and earthly to the weightless and transparent. This signature style emerged not in his early oil paintings (pre-1908) but later, in the watercolour and charcoal drawings that illustrate his masterpiece, The Prophet. Keyrouz describes this as a spiritual loop: an ascending movement from the earth met by a descending grace from the universal Mother to the world of Earth.

Notably, as Keyrouz points out, Gibran—through Barbara Young—resisted the term “symbolic” for his work, preferring to call it “the visible truth.” This aligns with his 1920 confession to Mary Haskell that when he draws, he does it unconsciously without knowing why. Conversely, when he writes, he is fully aware of what he is writing.

Gibran creates a fluctuating trinity where time, space, and eternity pour into three horizons: nature, the body, and the spirit. In his work, the nude is not merely a body but an embodiment of Nature itself; a nude within a landscape is a mother holding her child. This profound reverence for form as the materialisation of the soul explains his aversion to the emerging modernist movements like Matisse or Picasso. He found their abstractions shallow and devoid of the spiritual essence he believed form must contain. As Samir Attallah wrote in The Art of Kahlil Gibran (1980), "One must therefore understand his parables before one can understand his drawings. It was his way of expressing his inner life and inciting others to express theirs."

In Man and Poet" (1998), Suheil Bushrui and Joe Jenkins indicate that in "September 26 (1911) Gibran presented Mary with a painting which she named The Beholder. (...) she thought the painting marked 'the beginning of another ascent'." We may conclude that Paris was the focal point of his paintings. However, after Miss Keyes criticized his technique, Gibran replied in a letter to Haskell in The Love Story of Mary and Gibran (1911). The importance of his response lies in his discussion of his technique, style, and more.

I am not a creator of a theory which may or not be applicable - - - I have simply found myself one day this summer gazing at a fundamental Reality in Life, which any man can open his eyes and gaze at.

Technique is a power that could only reveal itself through style... and my style is only a month old. It was born with the "Beholder" and I am trying to bring it up as a mother would bring up her baby, I am trying to make it an instrument, a language, through which I will be able to express myself fully. Most people are apt to say that the technique is bad when they do not like the style of a work of art - - and to like or to dislike a style is a matter of temperament. ... I know too well what is wrong in my work and I am trying to make it right - but Miss Keyes dose not know - and she thinks it is the technique. But I am almost sure that even when my style or technique becomes perfect Miss Keyes will not like my work... She also said that my lights are good but my shadows are bad - That, too, is a funny, illogical statement; for how could anybody produce good lights without having good shadows?

Light, on a flat surface, is nothing but the absence of shadows. Good light, in a picture, is an optic illusion produced by good shadows. She probably wanted to say that those heads were out of construction, badly drawn, lacking in form... I hope that I shall always be able to paint pictures that will make people see other pictures (men-tally) out beyond the left or right edge. I want every picture to be nothing but a beginning of another unseen picture.

The discussions and critics over Gibran's artworks never stopped. The exhibition, which opened on Monday, January 29, 1917, marked a new breakthrough in his artistic career, and recognition at last appeared. His work was beginning to be appreciated by some of the most perceptive minds in New York. Alice Raphael Eckstein, a leading art critic and scholar of Goethe, wrote: An illuminating beauty informs his work; to him the idea becomes beautifulif it is true; the emotion becomes truth if it is real.

In New York, 2023, Claire Gilman, chief curator at The Drawing Center and organizer of the exhibition "A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran" claimed that he abandoned painting in 1912, probably because he was a much better draftsman than a painter. Did this have anything to do with his statement to Misha (Mikhail Naimy): "I'm a false alarm"?

I asked several professional painters about Gibran's style, and they concurred that his academic technique progressed during the post-Paris period. They acknowledged that, despite similarities to Blake, Gibran developed his own distinct style. Both artists convey the same theme of the spiritual inner self, each from their unique perspective, much like the relationship between Picasso and Braque.

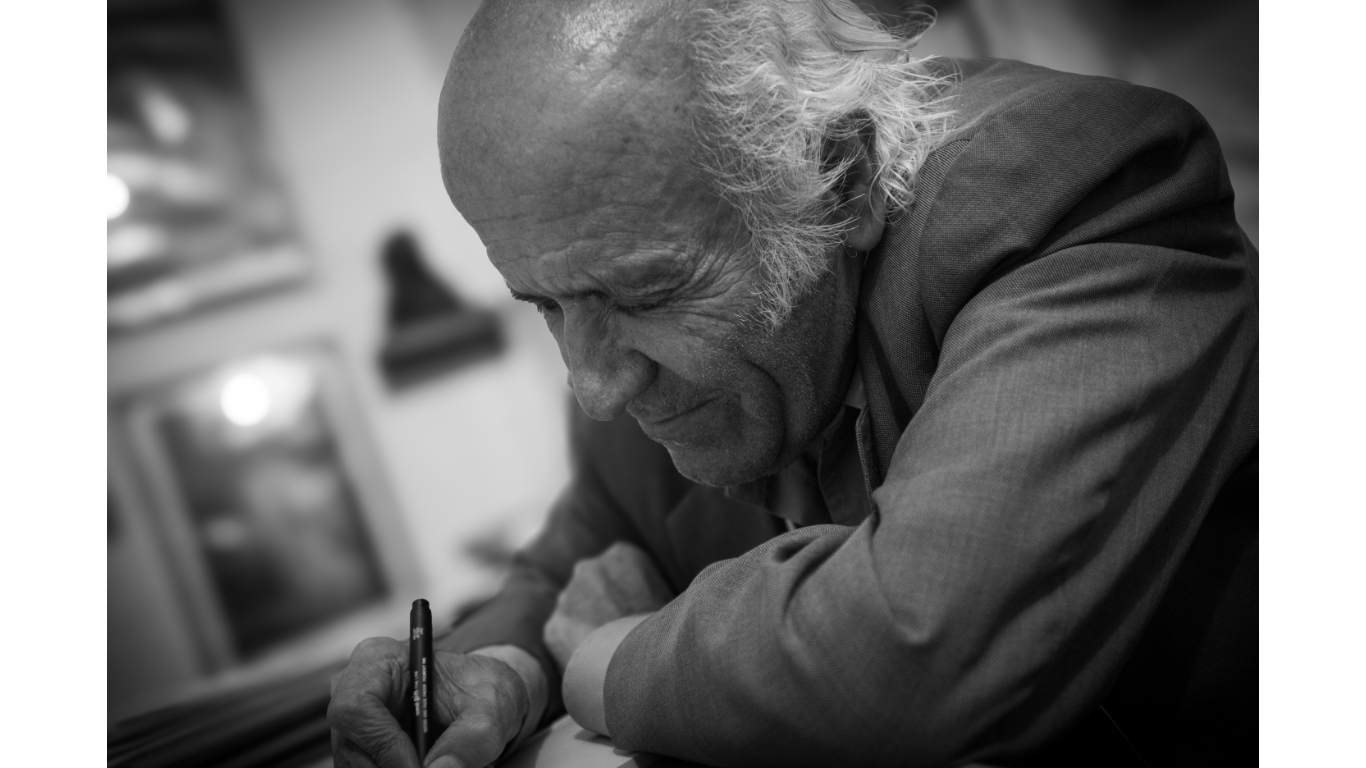

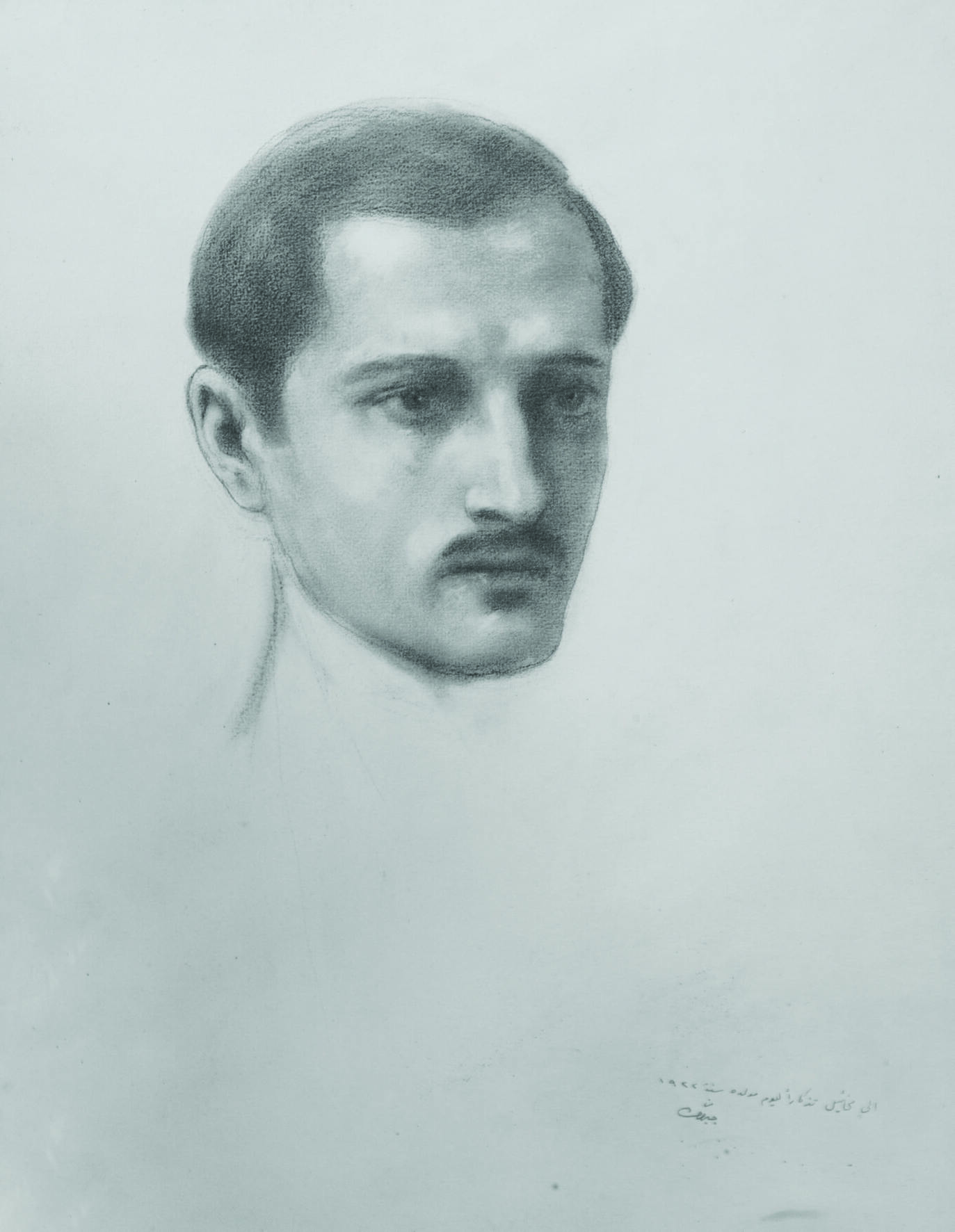

This "philosophy" extended to his portraiture. For Gibran, the face was a marvelous mirror of the innermost soul. I personally experienced this when I saw the portrait that Gibran made a birthday gift to his friend Misha (1922). The artwork radiates a palpable, tender affection that a mere photograph fails to convey.

When Gibran finished Albert Pinkham Ryder’s portrait, Ryder said : "Wonderful work.You've drawn what's inside me – the bones and the brain." in Man and Poet, Suheil Bushrui and Joe Jenkins (1998).

Gibran drew on whatever was at hand—typewriter paper, restaurant napkins—and rarely signed his works, believing their style would forever identify them. According to Robin Waterfield’s biography Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran (1998), oil was his preferred medium between 1908 and 1914. However, before and after this period, he primarily worked with pencil, ink, watercolour, and gouache.

For his magnum opus, The Prophet (1923), he chose the two most extreme mediums: the demanding mastery of watercolour for the book’s illustrations, and the primal simplicity of charcoal pencil for the face of his protagonist, Almustafa. This was no arbitrary decision. Gibran selected a humble, elementary material to reflect the humble, wise essence of the prophet, suggesting that for him, technique was always subservient to truth.

A defining element of Gibran’s style is the pervasive presence of mist, fog, and clouds. Professor Keyrouz insists that “His paintings almost never lack a horizon of translucent, cloud-like ether... the living ether... After the spirit departs the body, it settles in a gentle, cloud-like envelope that surrounds the harsh physical world... it remains for a period of time within that envelope” (ibid). This was not just a visual motif but a profound symbolic - “visible truth”- element that Gibran explored relentlessly in his writings. He felt a deep kinship with the mist, writing to Haskell in March 22, 1924: “I Think and Think and dream of distant places, and of Things with-out form like the mist. Sometimes I myself feel shapeless. It is a strange consciousness. I feel as if it were the consciousness of a cloud before it becomes rain or snow.”

A defining element of Gibran’s style is the pervasive presence of mist, fog, and clouds. Professor Keyrouz insists that “His paintings almost never lack a horizon of translucent, cloud-like ether... the living ether... After the spirit departs the body, it settles in a gentle, cloud-like envelope that surrounds the harsh physical world... it remains for a period of time within that envelope” (ibid). This was not just a visual motif but a profound symbolic - “visible truth”- element that Gibran explored relentlessly in his writings. He felt a deep kinship with the mist, writing to Haskell in March 22, 1924: “I Think and Think and dream of distant places, and of Things with-out form like the mist. Sometimes I myself feel shapeless. It is a strange consciousness. I feel as if it were the consciousness of a cloud before it becomes rain or snow.”

This theme echoes throughout his work:

“The mist that drifts away at dawn, leaving but dew in the fields, shall rise and gather into a cloud and then fall down in rain. And not unlike the mist have I been.”

– The Prophet, “The Farewell”

In his letters to May Ziade he writes:

"Who, I wonder, can transform this gentle fog into statues and monuments? But the Lebanese girl who hears what is behind the sounds will see in the fog images and specters.”

– New York, February 7, 1919, The Blue Flame

“My life has become unified, and now I work in the fog, I meet with people in the fog, and I sleep and dream, only to wake and find myself still in the fog.”

– Boston, January 11, 1921, The Blue Flame

The poem from Sand and Foam continues this theme:

“A work of art is a mist carved into an image.”

“Once I filled my hand with mist. Then I opened it and lo, the mist was a worm.

And I closed and opened my hand again, and behold there was a bird.”

From The Garden of the Prophet 1932:

“If you would freedom, you must need turn to mist.”

“We must become mist once more and learn of the beginning.”

“In your meadows when the mist of evening half veils your way”

“Alone! And what of it? You came alone, and alone shall you pass into the mist.”

“We must become mist once more and learn of the beginning”

The Garden of the Prophet, the last book of Gibran, concludes with a powerful poem, “O Mist, my sister,” which can be interpreted as Gibran’s final artistic statement. It is like a return to formlessness, a merging with the universal. This motif is so central that I featured prominently in my exhibition Gibran, Tribute to the Motherland (Beiteddine Festival, 2015), and in The seeds Process (2025) a tour project with Glen Kalem Habib, in which I represent the mist as Gibran’s soul that is still floating, proceeding from the sea through the sacred valley and rebelliously challenging the highest peak in Lebanon.

O Mist, my sister, white breath not yet held in a mould,

I return to you, a breath white and voiceless,

A word not yet uttered.

“O Mist, my winged sister mist, we are together now,

And together we shall be till life’s second day,

Whose dawn shall lay you, dewdrops in a garden,

And me a babe upon the breast of a woman,

And we shall remember.

“O Mist, my sister, I come back, a heart listening in its depths,

Even as your heart,

A desire throbbing and aimless even as your desire,

A thought not yet gathered, even as your thought.

“O Mist, my sister, first-born of my mother,

My hands still hold the green seeds you bade me scatter,

And my lips are sealed upon the song you bade me sing;

And I bring you no fruit, and I bring you no echoes

For my hands were blind, and my lips unyielding.

“O Mist, my sister, much did I love the world, and the world loved me,

For all my smiles were upon her lips, and all her tears were in my eyes.

Yet there was between us a gulf of silence which she would not abridge

And I could not overstep.

“O Mist, my sister, my deathless sister Mist,

I sang the ancient songs unto my little children,

And they listened, and there was wondering upon their face;

But tomorrow perchance they will forget the song,

And I know not to whom the wind will carry the song.

And though it was not mine own, yet it came to my heart

And dwelt for a moment upon my lips.

“O Mist, my sister, though all this came to pass,

I am at peace.

It was enough to sing to those already born.

And though the singing is indeed not mine,

Yet it is of my heart’s deepest desire.

“O Mist, my sister, my sister Mist,

I am one with you now.

No longer am I a self.

The walls have fallen,

And the chains have broken;

I rise to you, a mist,

And together we shall float upon the sea until life’s second day,

When dawn shall lay you, dewdrops in a garden,

And me a babe upon the breast of a woman.”

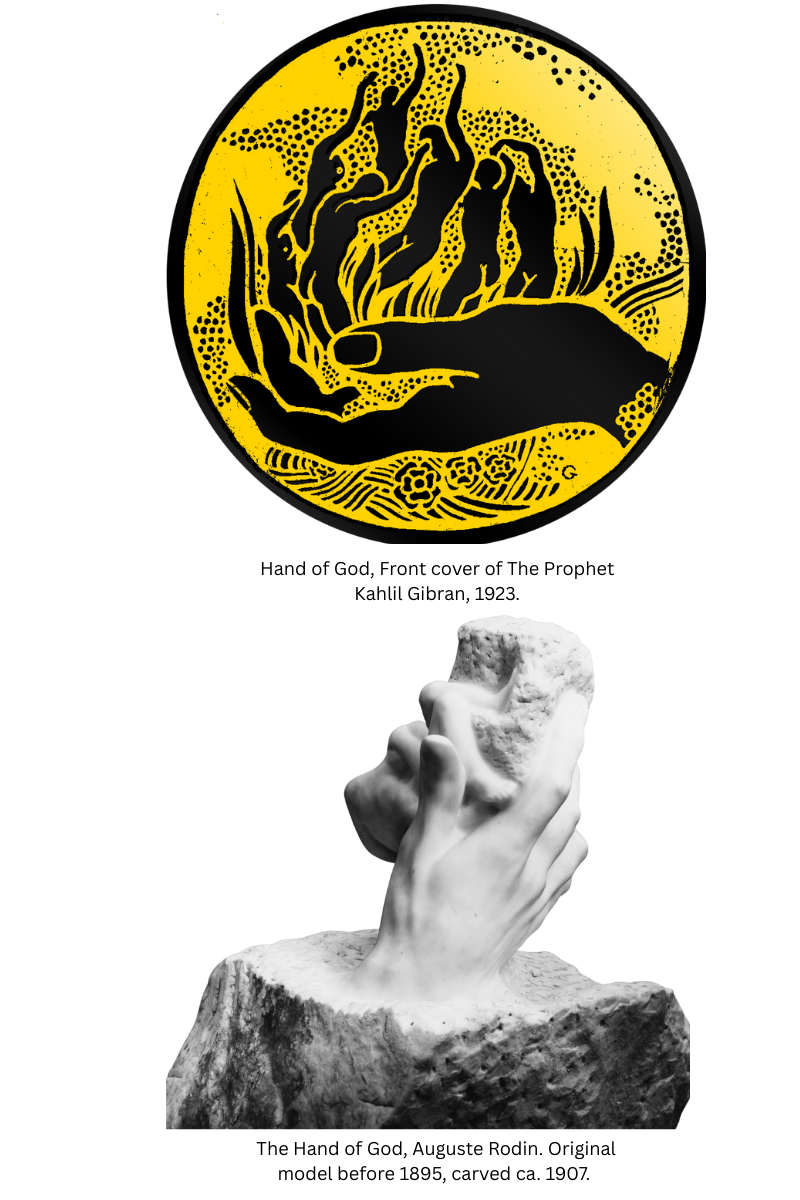

The hand of God… was so handy

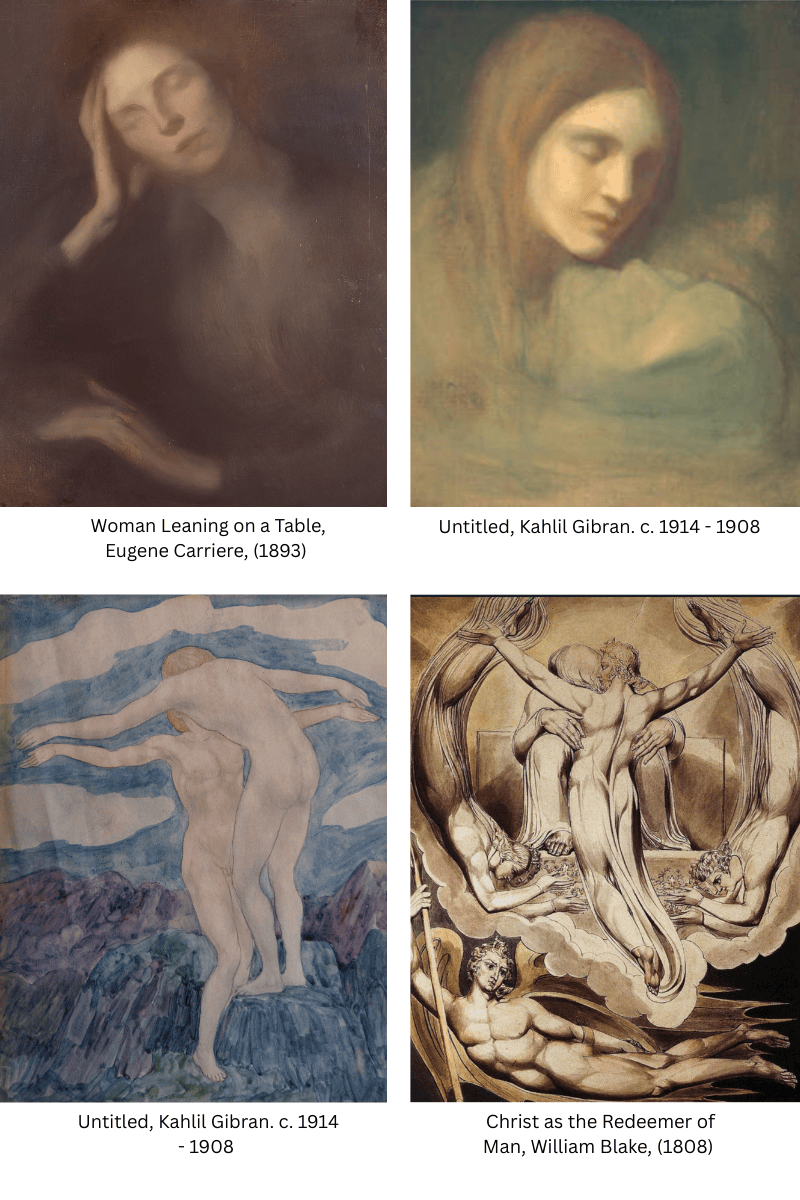

Ultimately, Gibran synthesised elements from Blake, Carrière, Rodin, and Nietzsche on his palette to forge his own world vision (See below for compared artworks). What makes his work uniquely “Gibranian” is its simplicity and poetic charm, but also its profound emotional immediacy. Gibran’s works, whether made from words, coulours, or light, reach our ARCHETYPES, and that is the essence of his success.

Is Gibran the creator of a new style like Cubism? I believe not. In 1909 he wrote to Haskell, The flames within us must take beautiful shapes otherwise they burn us. Gibran was seeking a form to incarnate this fire within him. As a believer in reincarnation, he had no qualms about using the forms of others to embody his inner world. Many of his paintings were unsigned, and his first aim for galleries was not to sell his artwork but to share it with the public. The paintings were only a means, what mattered to him were the Stars not the finger that points at them.

His work was a lifelong pursuit, not merely a “passing mood.”

1. The Mist driving the offroad of Bsharri (authors)

2. The Hand of God, Auguste Rodin. Original model before 1895, carved ca. 1907. Met Museum.

3. Front cover of The Prophet Kahlil Gibran, 1923. New York, A.A Knopf Publishers

4. Newton, William Blake. (circa -1804). https://www.blakearchive.org/

5. Untitled, Kahlil Gibran (pre 1914) Kahlil Gibran Museum

6. The Reunion of the Soul & the Body, from The Grave, a Poem by Robert Blair,

William Blake. (1913). https://www.blakearchive.org/

7. The Flame, Kahlil Gibran Harvard Art Museums

8. Woman Leaning on a Table, Eugène Carrière, (1893)

9. Untitled, Kahlil Gibran. c. 1914 - 1908 Telfair Museum of Art

10. The Being and his Aura, Kahlil Gibran, Kahlil Gibran Museum

11. Christ as the Redeemer of Man, William Blake, (1808) https://www.blakearchive.org/

12. Untitled, Kahlil Gibran, (pre 1914) Kahlil Gibran Museum

13. Pity, William Blake, Ca, 1795, The Metropolitan Museum of Art,