-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Francesco Medici

All Rights Reserved © Copyright Francesco Medici 2025

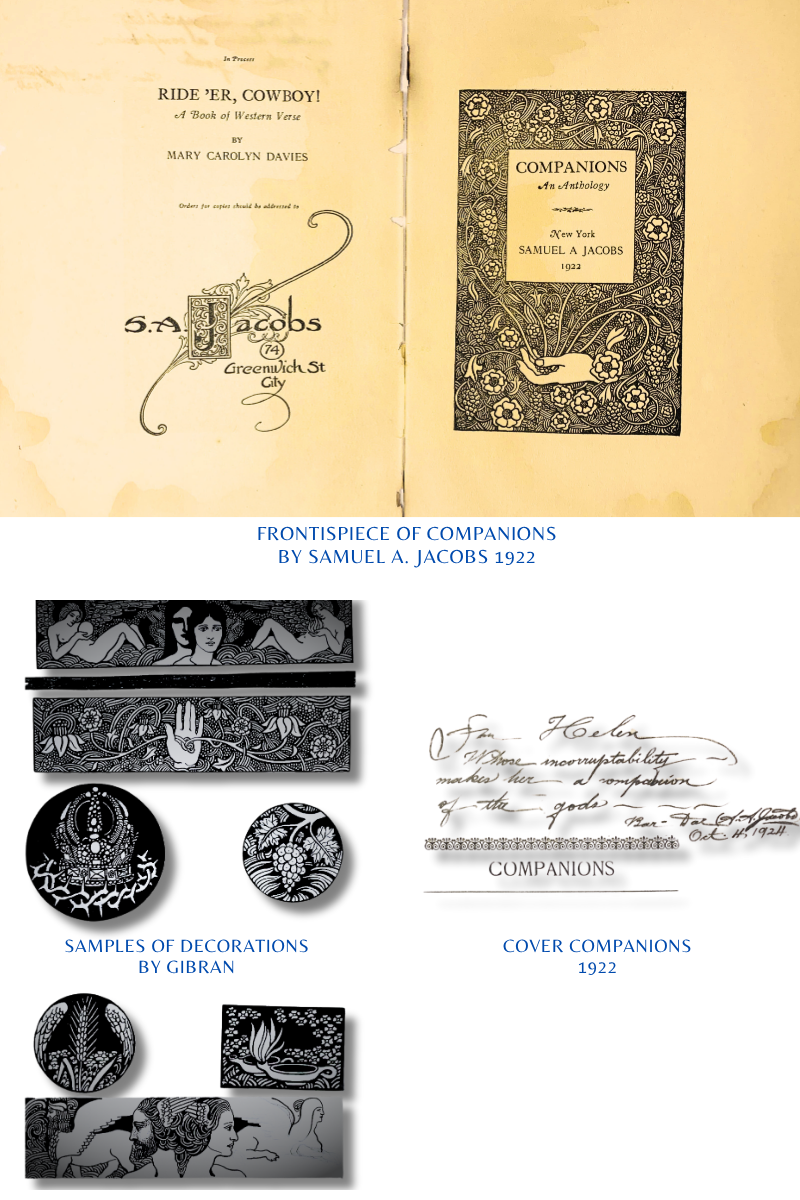

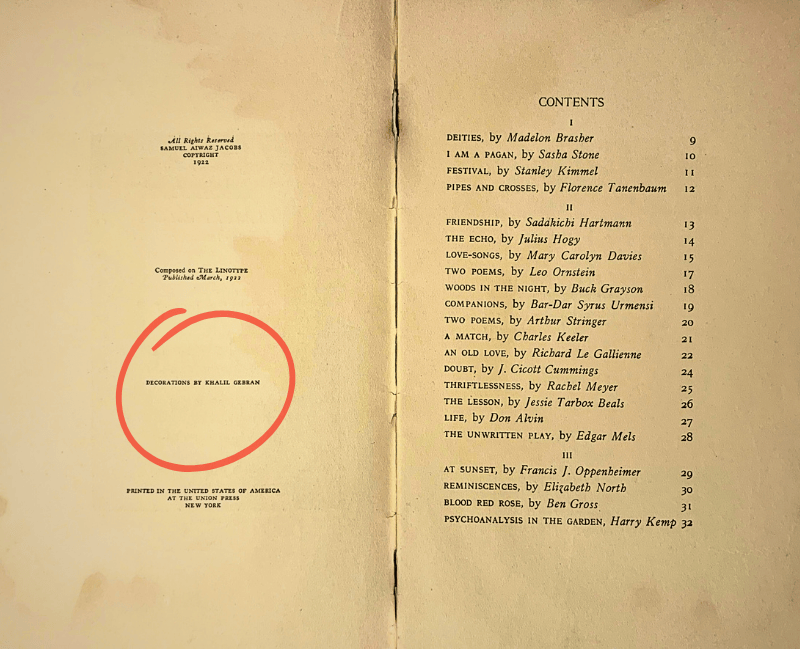

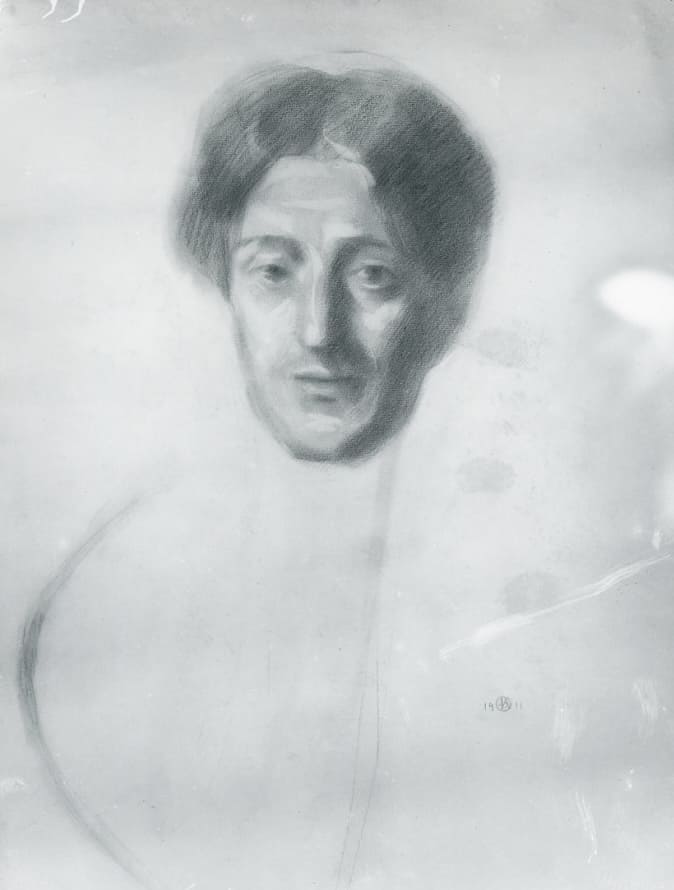

Between the late 1910s and early 1920s, Kahlil Gibran had nearly abandoned his “Temple of Art” portrait series, but he still enjoyed portraying his friends and decorating their books. For example, he had offered to illustrate Carl Gad’s Johan Bojer: The Man and His Works in 1920, and Witter Bynner’s The New World in 1922. In March of the same year, a precious and scarce volume of only 32 pages was published, that is hardly mentioned by the scholars and biographers of the Lebanese writer. It is an anthology of poetry entitled Companions, to which Gibran contributed as an artist by drawing the frontispiece and with some other little embellishments. For reasons that are unclear, his name in the facing title page was curiously misspelled as ‘Khalil Gebran.’

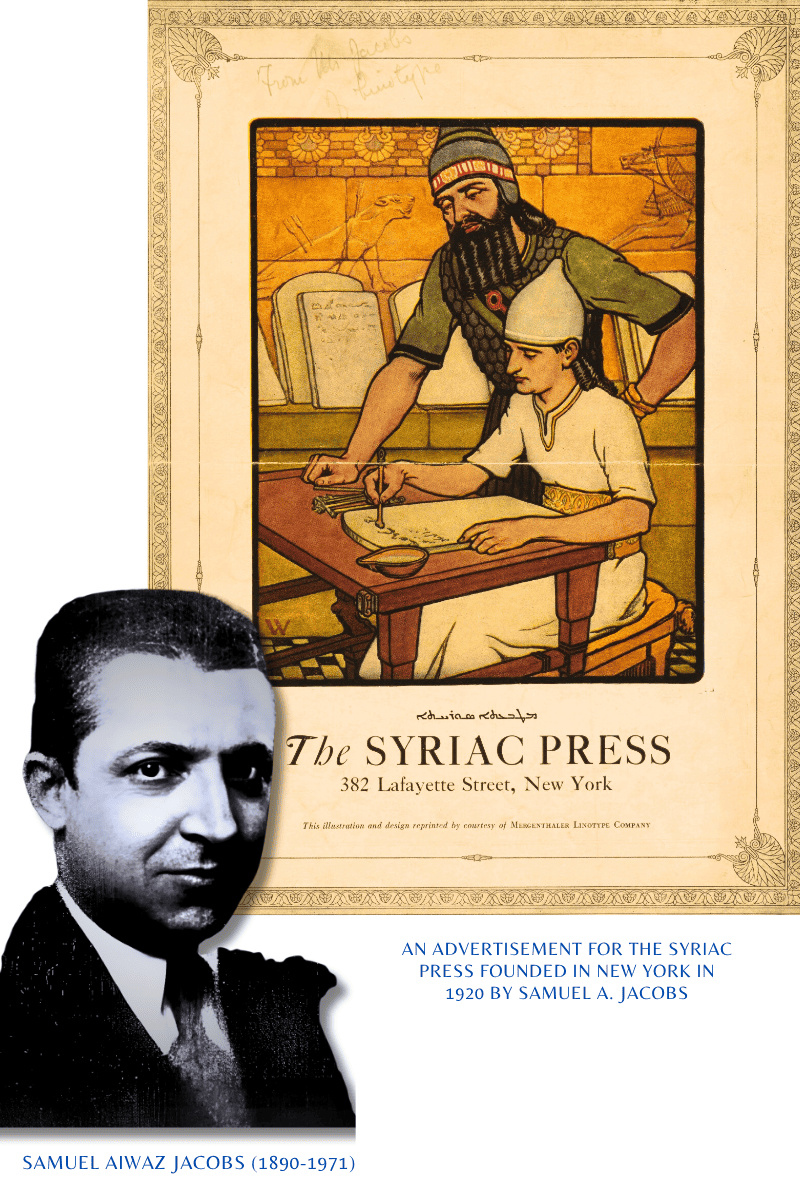

The booklet was privately printed in New York by a certain S.A. Jacobs, and includes a few more than twenty poems by as many authors, some of them pretty known, others less or completely unknown: Deities by Madelon Brasher, I am a Pagan by Sasha Stone, Festival by Stanley Preston Kimmel (1894-1982), Pipes and Crosses by Florence Tanenbaum (Florence Becker Lennon, 1895-1984), Friendship by Carl Sadakichi Hartmann (1867-1944), The Echo by Julius Hogy, Love-Songs by Mary Carolyn Davies (1888-1974), Two Poems by Leo Ornstein (1893-2002), Woods in the Night by Buck Grayson, Two Poems by Arthur John Stringer (1874-1950), A Match by Charles Augustus Keeler (1871-1937), An Old Love by Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947), Doubt by J. Cicott Cummings, Thriftlessness by Rachel Meyer, The Lesson by Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870-1942), Life by Don Alvin, The Unwritten Play by Edgar Mels, At Sunset by Francis Joseph Oppenheimer (1881-1973), Reminiscences by Elizabeth North, Blood Red Rose by Ben Gross, Psychoanalysis in the Garden by Harry Hibbard Kemp (1883-1960). The poem Companions, that gives the sylloge its title, is by Jacobs himself, who signs it with the obscure and evocative pen-name ‘Bar-Dar Syrus Urmensi,’ which translates as ‘Bar-Dar the Syrian/Assyrian, the Urmian.’ Who was that mysterious man? And how did Gibran get to know him?

Shmu’el bar ‘Aiwaz d-bet Ya‘qub, i.e., ‘Samuel, son of Aiwaz, of the House of Jacob’ (according to other sources, Shmu’el bar Hammurabi Ya‘qub, or Shmu’el ‘Aiwaz Shirabadi Azerbayjani Morad Khan) was born to an Assyrian family in northwestern Iran on 12 February 1890. His birthplace, the village of Shirabad, is located north of Urmia, along the Nazlu river (Nazlou Chay), West Azerbaijan Province. His parents encouraged him to study to the highest level of education available to anyone in the Iran of his day. He attended the Urmia College (also known as Qalla School), which was the boys’ school established by American missionaries in 1836. He studied in the newly introduced program in technical subjects, which was part of the late 19th-century expansion of the training that had previously prepared students only in the liberal arts, theology, and medicine. Technical training, a precursor to engineering education, allowed him to learn to operate linotype printing machines, which was a new technology replacing manual, letter-by-letter typesetting. From his boyhood, he showed a deep fascination with the layout and dynamics of different scripts upon book and manuscript pages.

In 1906, at the age of fifteen, he emigrated to the United States, where his name was registered as Samuel Aiwaz Jacobs. He furthered his education in Worcester, Mass., and began to practice printing, including his own poetry. In 1914 he moved to New York City and in 1915 went to work for Rev. Joel E. Werda (1868-1941) – Baptist minister, translator of the English Bible into Assyrian, and editor –, linotyping for his bilingual (Assyrian/Neo-Aramaic and English) weekly newspaper, the “Persian-American Courier” (later renamed the “Assyrian American Courier”). In 1916 Jacobs linotyped a translation into Neo-Aramaic (‘modern Syriac’) by Abraham Yohannan (1853-1925) of the classical Syriac Ktaba d-Marganitha (Book of the Pearl on the Truth of Christianity) by Mar Abdisho bar Berikha, or Ebedjesu (known as St. Odisho in English, d. 1318), Metropolitan of Nusaybin and Armenia, a work that is considered one of the most important ecclesiastical texts of the Assyrian Church of the East, a kind of theological encyclopaedia. On the title page of the book, Jacobs called his press in Neo-Aramaic “Matba‘ta d-bet Ya‘qub” (“House of Jacob Press”). He also published a guidebook for Assyrian immigrants.

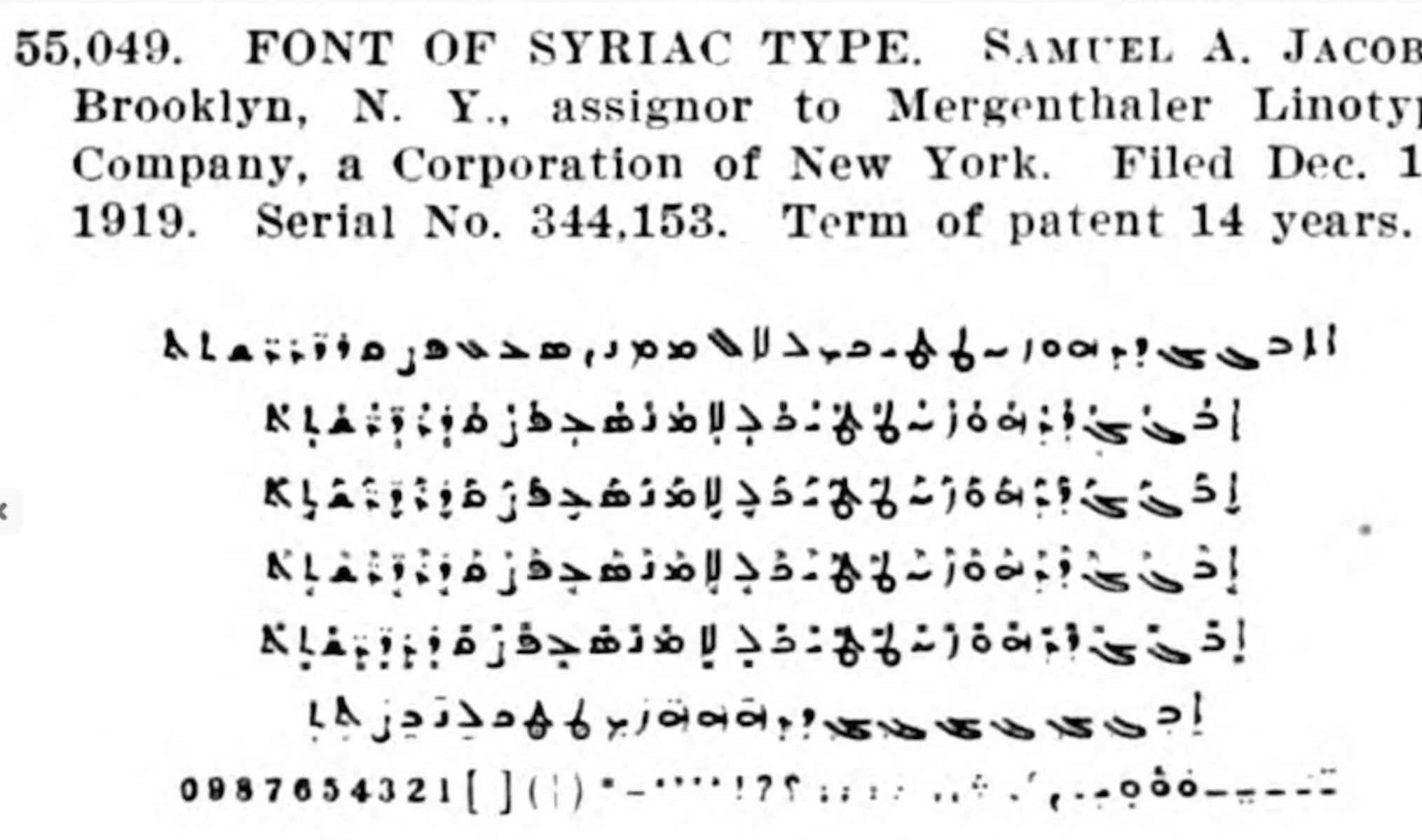

In December 1919, Jacobs filed applications for patents, on “decorative Syriac fonts” and on a “typographical element” for combining letters and diacritics. Upon receiving his font patents in May 1920, he transferred their ownership to the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, the leading linotype company in the United States. There he began a career in printing, designing and revising unusual type faces, developing his talents in multilingual typography, and his contribution paved the way for more people to publish in Assyrian. In those years, he married a woman named Hilda, a proofreader who worked with him. The couple had one son, Sam[uel] Jr.

In 1922, he established Polytype Press in Greenwich Village, and Companions was his first literary publication. It was probably their mutual friend Richard Le Gallienne, included in the anthology, who introduced Jacobs to Gibran – the latter had portrayed the English author and poet resident in the United States for his “Temple of Art” in 1911. As for Jacobs’ pseudonym Bar-Dar (or also, Bardar, as in the case of ‘Bardar Urmensi Persidis,’ i.e., ‘Bardar, the Urmian, the Persian’), it has no meaning in Aramaic and has been thought to imperfectly render Persian barādar, i.e., ‘brother.’ But the hyphenated form in print seems, rather, or additionally, to suggest Persian bar dar, i.e., ‘upon [the] door,’ or, bar dār, i.e., ‘crucified’ – in short, a sort of word play.

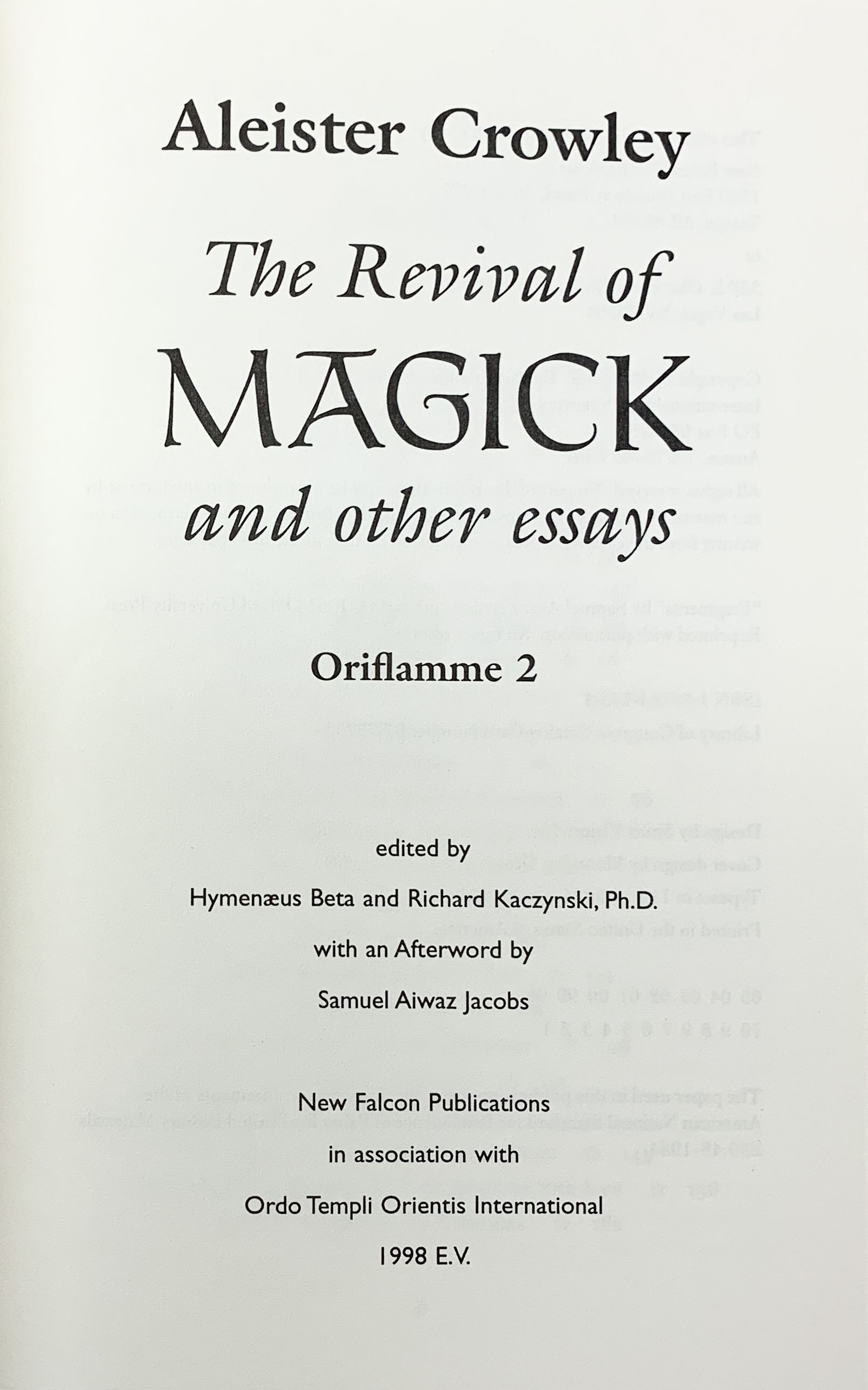

On the other hand, it is known that Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) had an interest in Jacobs’ patronymic Aiwaz, since it sounds close to the name of a non-corporeal being named Aiwass that the famous British occultist and satanist claimed communicated with him. The two men developed a relationship of mutual esteem and respect, and once, in an interview, Jacobs, probably teasing his interlocutor, stated that Aiwaz was “the Persian equivalent of Satan.” It may be interesting to recall here that some years before Crowley had reviewed Gibran’s The Madman (cf. The Equinox, vol. 3, no. 1, March 1919, p. 181):

I do not much care for the drawings in this book. They are messy, and rather conventional. But I like some of the parables very much indeed. It is not very sensible to compare Mr. Gibran with Blake, because Blake was a genius whose every act was wrought from the white heat of passion. This is a smaller fish swimming in shallower and calmer waters. The spirit is more French than Irish. However, he is short enough to speak for himself. Here is one of his parables:

THE SCARECROW

Once I said to a scarecrow, “You must be tired of standing in this lonely field.”

And he said, “The joy of scaring is a deep and lasting one, and I never tire of it.”

Said I, after a minute of thought, “It is true; for I too have known that joy.”

Said he, “Only those who are stuffed with straw can know it.”

Then I left him, not knowing whether he had complimented or belittled it.

A year passed, during which the scarecrow turned philosopher.

And when I passed by him again I saw two crows building a nest under his hat.

Here is another:

THE NEW PLEASURE

Last night I invented a new pleasure, and as I was giving it the first trial an angel and a devil came

rushing toward my house. They met at my door and fought with each other over my newly created

pleasure; the one crying, “It is a sin!” – the other, “It is a virtue!” Good boy!

Coming back to Jacobs, he is best known for typesetting the poetry books of E.E. Cummings (Edward Estlin Cummings, 1894-1962) – their profitable collaboration began in 1923 –, who used to call the first his “personal Persian typesetter/press agent.” Jacobs typeset the works of other American authors, such as the playwright, Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953), and the poet, Marianne Moore (1887-1972). He also designed numerous books for notable publishers including Covici-Friede, Boni & Liveright, Stratford Press, New Directions, Oxford University Press, and Dutton.

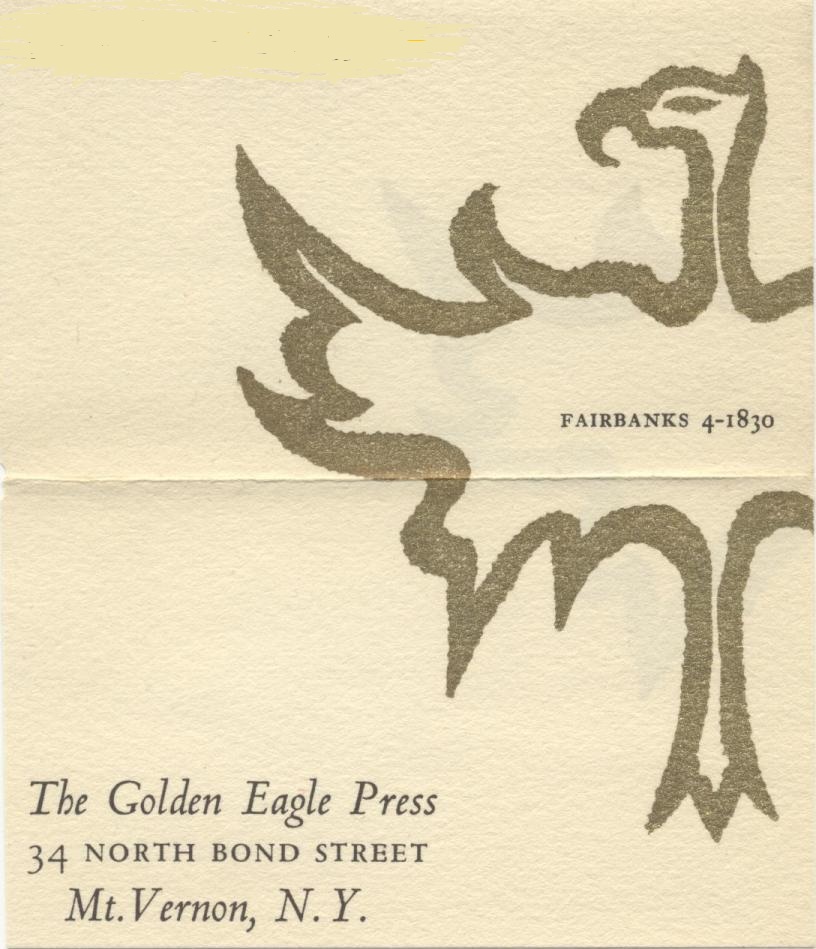

In 1934, he moved his Jacobs Established Polytype Press from the Village to Mt. Vernon, N.Y., renamed it the Golden Eagle Press, and continued to print fine, limited editions of significant literary works until he retired, in 1966. Being left a widower, he spent the last years of his life at the Sans Souci Nursing Home in Yonkers, N.Y. He died on 16 September 1971 at the age of 80 in Yonkers General Hospital.