-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

By Glen Kalem-Habib

Based on the published essay "ask not" by Enerst G. Tanis

Contributing writers Jean Pierre Dahdah PHD, Philippe Maryssael, Ray Jureidini, Francesco Medici

All rights reserved © copyright 2025

When I meet people for the first time and the conversation moves beyond the shallow waters of current affairs or my day job, I sometimes mention my connection to the late artist and poet Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931). The response is usually one of a few familiar refrains: "Oh yes, I read his poetry at university," or "His words were recited at our wedding." Even better is: "I've read The Prophet, but I don't know much about the author… Kaa-ill Gibb-ran!" I love these exchanges! Often, people walk away having learned a thing or two about Gibran from a guy who, more often than not, looks like your local tradesman—the kind who can fix a broken something.

On the other hand, as the founder and caretaker of the world's most informative Kahlil Gibran websites, I naturally receive a steady stream of email, requests mainly revolving around things like copyright, books, paintings, and the perennial question of why it's 'Kahlil' and not 'Khalil' or—better yet—why it isn't 'Gibran Khalil Gibran?'; you'd be glad to know we've published a piece on that, too!

Another common request from our webfarers is to verify poems or quotes, or—more accurately—misquotes. Take the following examples:

"Travel and tell no one, live a true love story and tell no one, live happily and tell no one, people ruin beautiful things."

You guessed it: not Gibran's. Then there's the poem labelled "Fear," which is all over the internet, attributed to him, but is more accurately linked to Osho, in whose book Beyond Enlightenment it appears.

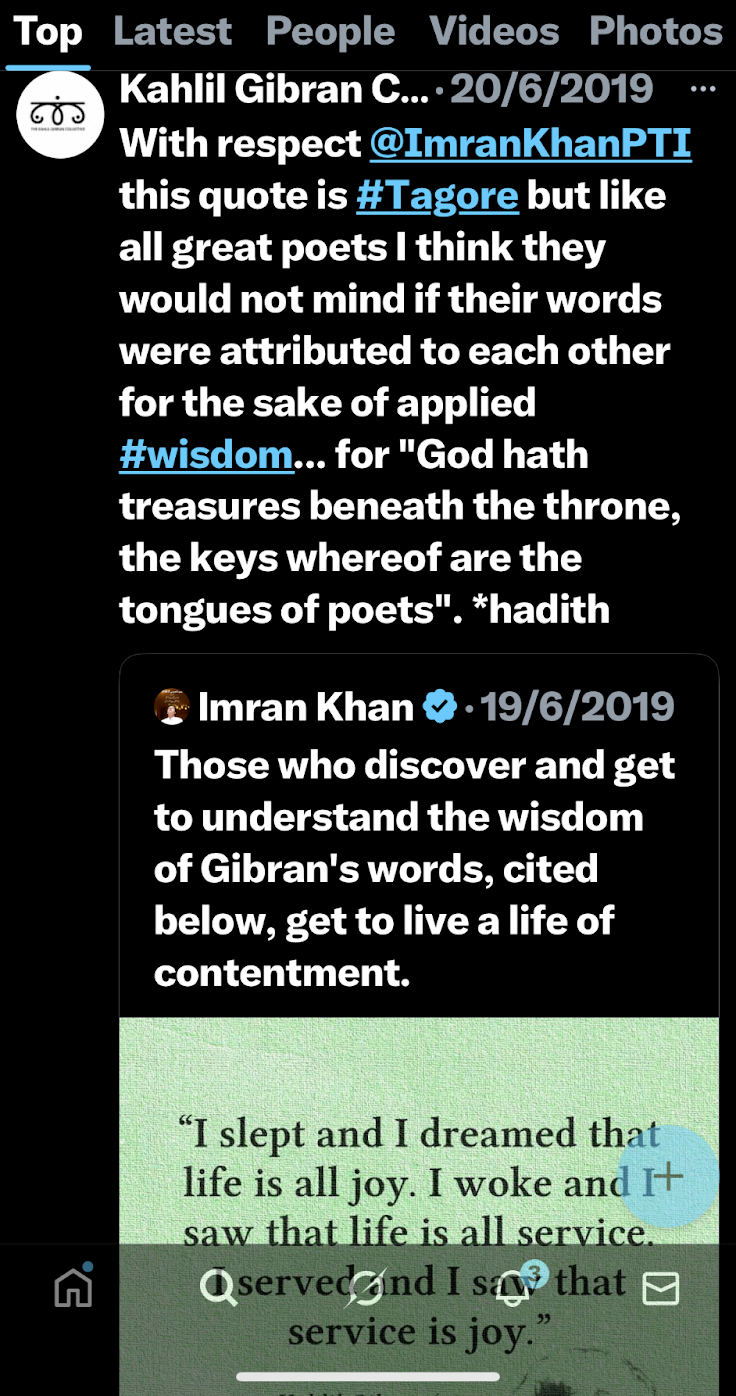

A couple of years ago, my Twitter, now X, account was tagged into a heated online debate, to which I was asked to verify the following quote:

"I slept, and dreamed that life was beauty; I woke, and found that life was duty. Was thy dream then a shadowy lie? Toil on, sad heart, courageously, And thou shalt find thy dream to be a noonday light and truth to thee."

As it turns out, Tagore fans were outraged that former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan had Tweeted this, wrongly attributing this quote to Gibran, instead of Tagore!

The most significant misquote, attribution which some have labelled an act of "patriotic plagiarism," has for decades linked one of Gibran's early Arabic political writings to John F. Kennedy's most famous line from his 1961 inaugural address.

"Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country."

This is a big one! and deserves one of my longest written essays on it, so buckle up, it’s a deep dive.

A disclaimer:

I should mention that I started writing this piece back in 2016 and have long debated when or if to publish it. Oh boy, this is going to break some hearts (mostly those of my fellow Lebanese diaspora), but it is time to finally lay out the findings for the record.

Arguably, it is one of the world's most recognised political quotes. In this essay, I summarise the known facts, the blatant fabrications and the bizarre coincidences attributed to this historical insight, linking two great figures from the global divide of East and West. My aim is to offer a clearer and more concise overview of the two "similar" quotes or ideas, their origins and how two unconnected historical figures became associated by a shared vision to change the conventional acquisitive mindset that had crept into the population. The task here is to ask "how" this controversy developed.

In December 2012, while speaking and attending the 2nd International Conference on Kahlil Gibran at the Maryland University College Park, I had the great pleasure in meeting and befriending Mr Ernest G. Tanis. A Canadian lawyer and mediation expert by profession, he had arrived at the conference with the results of a five-year investigation that would finally question what most thought to be true (including myself) for decades.

In his presentation entitled "Ask Not," Tanis provided for the first time factual evidence that questioned the association that JFK's famous saying was linked to Kahlil Gibran's 1921 Arabic essay entitled "The New Era." He stated that it was not an act of "patriotic plagiarism" but a mere coincidence that these two giant figures came up with a similar thought that led to the speculation about their link. Mr Tanis, like most other Gibran enthusiasts, thought that the "Ask Not" link was genuine, but one day, when questioned about its authenticity, he felt the urge to investigate what evidence, if any, had existed. Garnering little or no connection other than the hearsay of overzealous admirers, the seed of doubt was now well and truly activated by his legal mind and the quest to find the facts.

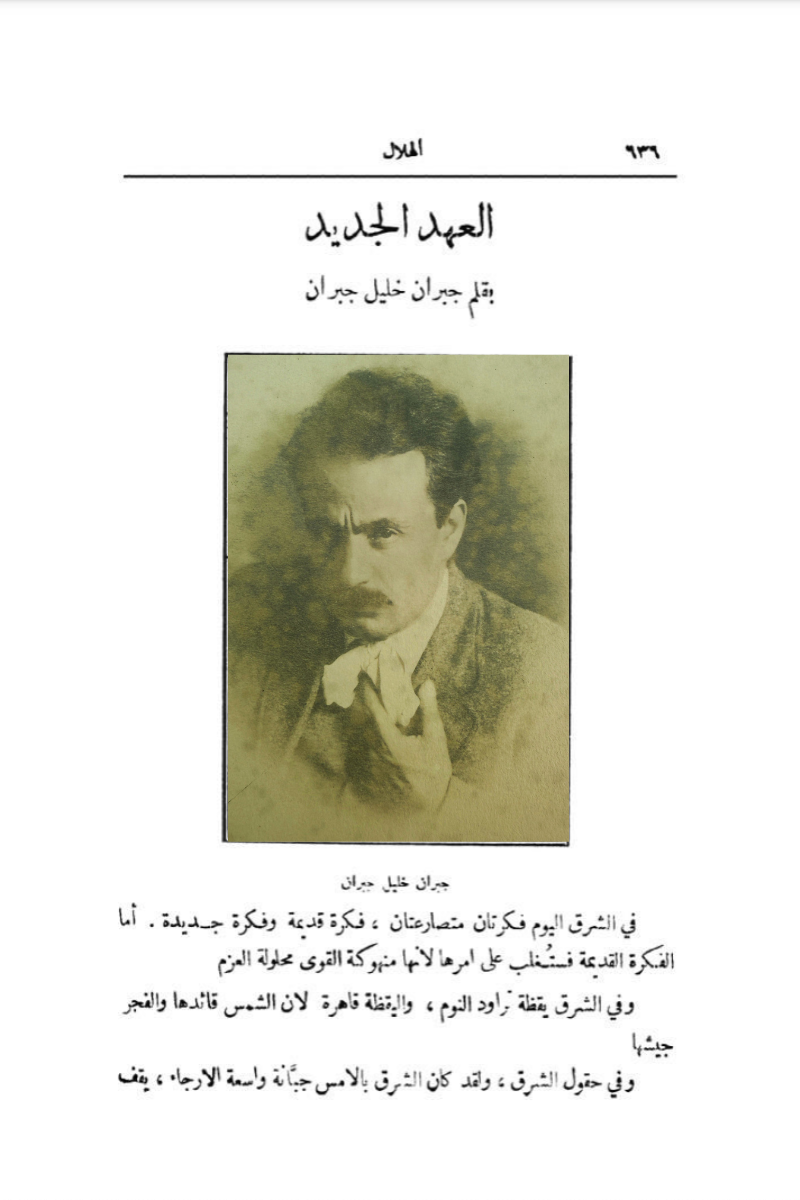

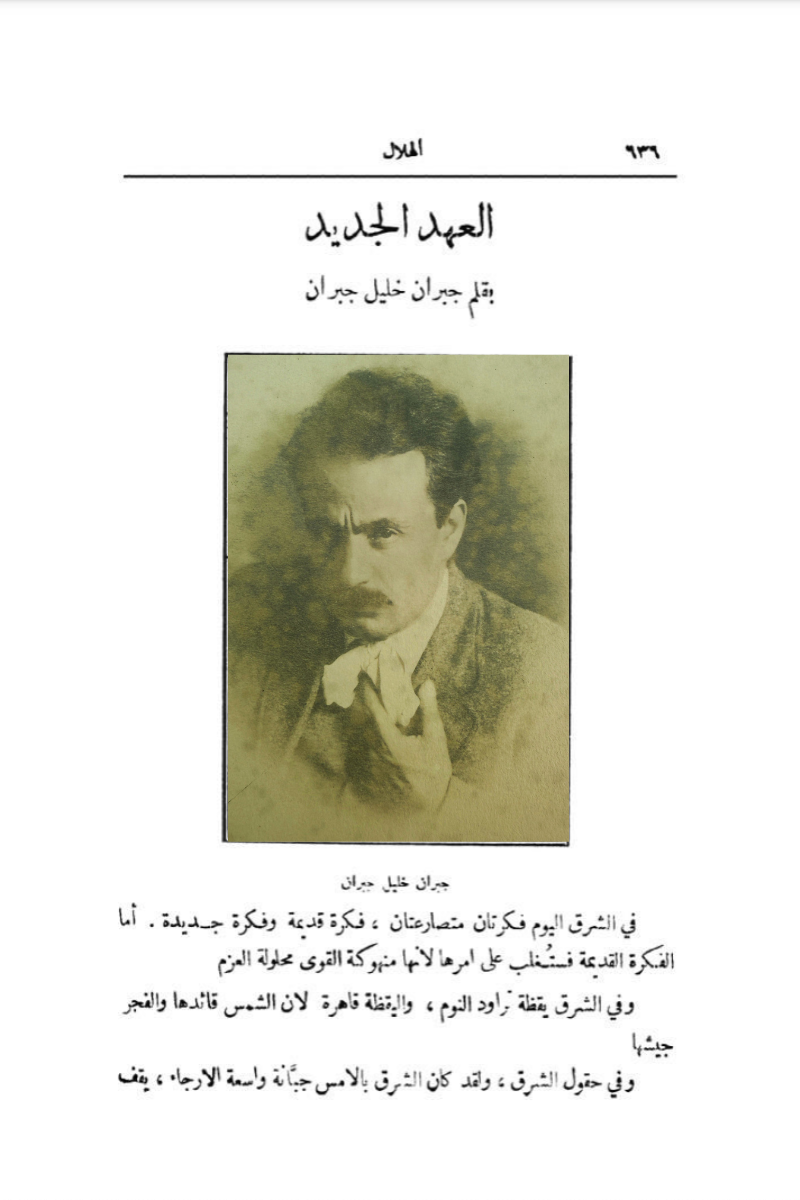

Borrowing from Tanis's published research paper, I summarise the historical facts that led to the misrepresentation of the two quotes, starting with a brief background on the origins of Gibran's 'similar' quote that was published in the Egyptian magazine, Al-Hilal on April 1, 1921 (not 1925 as wrongly noted by some scholars).

Let us begin with a brief biographical sketch on both men. Kahlil Gibran entered the world as Gibran Khalil Gibran on January 6, 1883, in the small, mountainous village of Bsharri in northern Lebanon. In 1895, his family emigrated to the United States, finding a home in Boston's South End. His education spanned continents, with formative periods spent in Beirut and Paris, before he ultimately settled in New York City's Greenwich Village for the remainder of his life. While his 1923 masterpiece, The Prophet, remains his most famous work, Gibran's primary identity was that of a painter. He left behind a staggering legacy of over 800 artworks, an incredible feat for a life cut short at 48 years.

John F. Kennedy was born in 1917 into the wealthy and politically driven Kennedy family of Brookline, Massachusetts. He was just four years old when Kahlil Gibran wrote The New Era in 1921, and a mere thirteen at the time of Gibran's death in 1931. The historical context makes a connection unlikely: during Gibran's final years, a young JFK was a sickly and often isolated teenager, battling severe, undiagnosed health issues, yet also cultivating a keen interest in history and writing. He also was an avid sportsman, dedicated Scout, he was known to possess a rebellious streak at the Canterbury School, so the likelihood of this particular boy journeying to smoke hookah and discuss geopolitics with Gibran in New York's Little Syria is highly unlikely; a better image would be one that envisions JFK smoking, reading one of his favourite books, Arabian Nights in sanctuary of 'The Hasty Pudding Institute of 1770.'

Kahlil Gibran's 1921 essay must be understood within the turbulent context of its time. Although he was already an established author in English, Gibran deliberately chose to write this piece in Arabic to address the urgent political situation unfolding in the Middle East.

The Arab world was in a state of profound transition. World War I had ended just three years prior, and the 400-year reign of the Ottoman Empire over Greater Syria was dissolving. In this power vacuum, Gibran and other Arab intellectuals fervently advocated for self-rule. His beloved Lebanon was at the very heart of this struggle.

The driving force behind this movement is captured by biographers Suheil Bushrui (1922-2015) and Joe Jenkins in their book, Kahlil Gibran: Man and Poet. They describe the energy championed by Ar-Rabitah (The Pen Bond), a small but influential group of Arab-American writers in New York to which Gibran belonged. They explain:

Composed of a small and rather select group of avant-garde men of letter who, under the guiding spirit of Gibran, became "an accomplished school in action", embarking on an adventurous literary experiment that effected a historic shift of emphasis in hitherto accepted Arabic literary excellence.

Gibran acted as the theoretician and literary expert, with well-defined aims, quickly and forcibly striking the Arab world as an independent literary school, an "academy of Arab letters" in New York. Newspapers and magazines in the Arab world, especially al-Hilal in Egypt, were excited by the novelty and revolutionary spirit of Arrabitah literature, which began to reproduce it at home.

The movement started to symbolize a new literary era for an Arab world already on the move. Its influence on modern Arabic literature was to be profound, and observers of this new movement called it a source "of illumination to an Arab life beginning to awake"; "the strongest school that modern Arabic literature has known"; and "an accomplished school in action."

Mikhail Naimy, one of Gibran's closest friends and a member of Arrabitah, sums up the success of the movement:

No member of Arrabitah could at that time foresee how the Arab world would develop, although many Syrians, both Christian and Muslim, felt betrayed by the West which after the fall of the Ottoman empire in 1918 had given repeated assurances of Arab independence as a reward for Arab assistance in defeating the Ottoman armies.

In light of all this energy, essays like Gibran's The New Era were born.

In 2007, Mr. Tanis embarked on a five-year investigation into this misattributed quote. His primary goal was to determine whether it could be linked to the original 1921 essay mentioned previously. His research ultimately exposed a series of inaccurate conclusions and factual errors, leading him to a central finding:

"The Kennedy quote is original, as is the Gibran quote… [They], like others before Kennedy, are similar in meaning, but all independently written."

Initially, the uncanny parallels between the quotes suggested a deep connection. Yet as Tanis delved deeper, ambiguous dates and bizarre allegations began to surface. The further he mined the history of both quotes, the more he questioned their supposed link—and any other connection for that matter.

For context, the summary of dates below is essential to understanding this investigation. I will elaborate on these timelines, as they provide key evidence supporting the strength of the study and its conclusion.

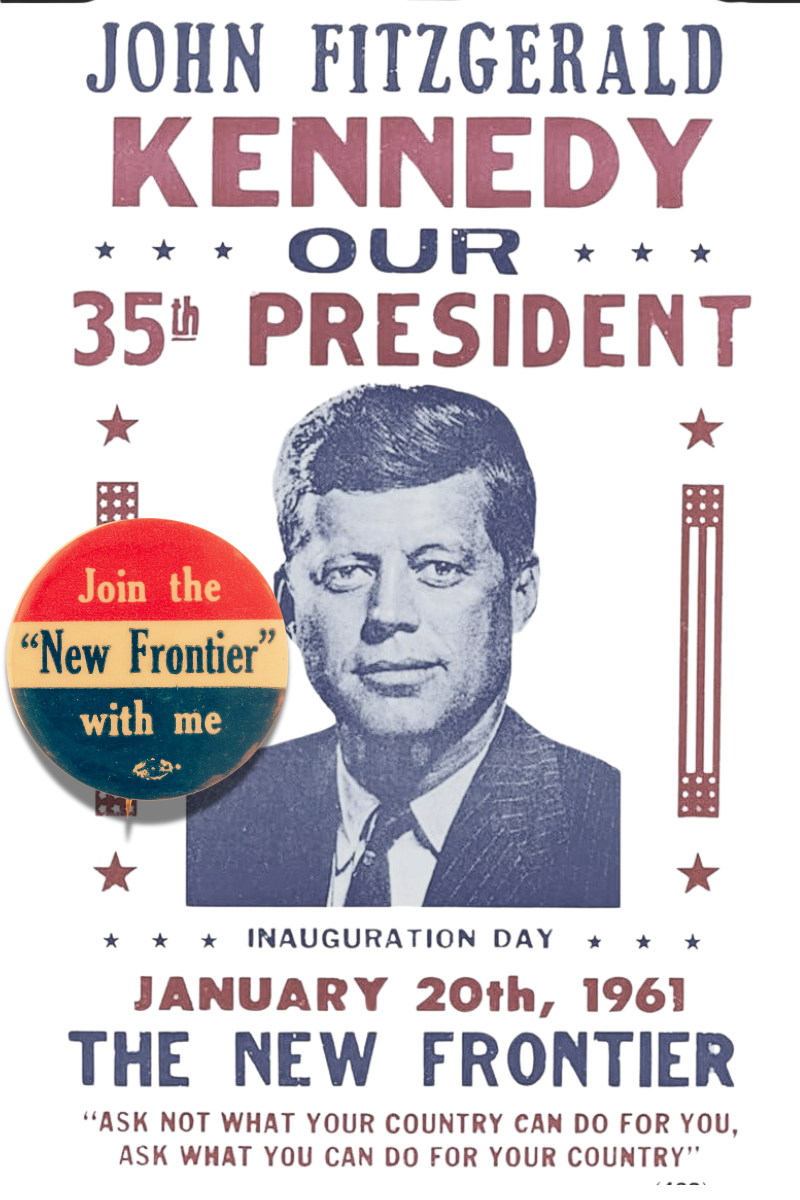

John F. Kennedy's 1960 presidential campaign adopted the slogan The New Frontier. While this theme is most famously linked to the Space Race against the Soviet Union, it encompassed a broader set of domestic and foreign policy ambitions.

Almost four years after Kennedy's campaign, a 1965 translation of Gibran's essay by Joseph Sheban appeared under the conspicuously similar title, The New Frontier. According to Tanis, Sheban deliberately chose this title to exploit its association with the late president. This newly translated essay thus became the root source of the confusion, leading many to innocently misrepresent the link between Gibran and JFK.

Crucially, in his introduction to this specific Gibran verse, Sheban presents the alleged connection to Kennedy not as a scholarly finding but as an assertion, offering no evidence to support his claim. He directly writes:

On the walls of many American homes hangs a plaque commemorating the statement of the late President John F. Kennedy: Ask not what your country can do for you, but ask what you can do for your country. This statement appeared in an article written by Gibran in Arabic, over fifty years ago. The heading of that article can be translated either "The New Deal" or "The New Frontier."

When the Gibran Society pressed about the connection to Gibran's writing, the JFK camp legitimately argued that the chronological timelines do not align: the English translation of Gibran's work was published in 1965, while Kennedy delivered his inaugural Ask not speech in 1961.

Furthermore, JFK's staff and historians have noted that the president himself allegedly wrote the Ask not speech and not his speechwriters, and as far as we know, JFK did not read Arabic. Therefore, he could not have paraphrased Gibran's 1921 essay.

Adding to the above debate—and not mentioned in Tanis's essay—I discovered a 1978 New York Times interview by Bob Levey with Robert Hill Murray offering another possible clue to the origins of JFK's speech.

Murray was a retired soldier who became a writer for the Voice of America (VOA) and a close friend of Robert F. Kennedy. He claimed to have inspired JFK's Ask not speech, despite having never met or served under the president. In the interview, Murray explains that JFK asked him to "prepare a list of 1,000 of his best slogans and phrases." According to Murray, one of those was drawn from Alexander the Great’s inaugural address of 336 B.C.:

"And you, trusted few, seek not to benefit from the bounty of war, nor from what your eyes feast upon within this land, …diligently seek, rather, in your hearts what you, as faithful believers in our cause, can bring to this, our fresh new world's horizon."

Impressed by the list, RFK allegedly told Murray in secret weeks later that JFK was running for President and asked him "to permit JFK to look over the list of slogans and proverbs for his own use and adaptation." Murray agreed.

The larger issue in determining the phrase's origin is that JFK never footnoted his inaugural speech. We will probably never know its exact source. Tanis sums this up nicely by saying:

Everyone hears and reads things throughout their lives, which somehow influence them, consciously and unconsciously. But to assert unequivocally that the famous "Ask not..." quote from President Kennedy was taken from any previous quote is not supported by any type of historical or literary analysis.

It is, however, fair to say that just as there were great writers of Western literature who wrote a similar thought, so, too, should there be acknowledgement of writers from the East, in this case, Gibran, who originally penned a similar phrase as President Kennedy; no more, no less. Gibran should be provided the same credit that Holmes was given.

In his memoir, JFK's main speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, reflects on the power of a well-timed speech, and user the Gibran quote as an example, he states:

The right speech, delivered at the right time by the right speaker, can ignite a fire, change men's minds, open their eyes, alter their views, bring hope to their lives and, in all these ways, change the world.

"Interestingly, decades later, the Kahlil Gibran Society pointed out that Gibran—a renowned poet, whether Lebanese or Persian, they were unsure—had written something very similar in his popular book The Prophet. They noted this work first appeared in the 1920s but had not been widely available in English by January 20, 1961. They also inquired if either Kennedy or Sorensen had knowledge of Persian or Arabic, to which Sorensen replied that they did not."

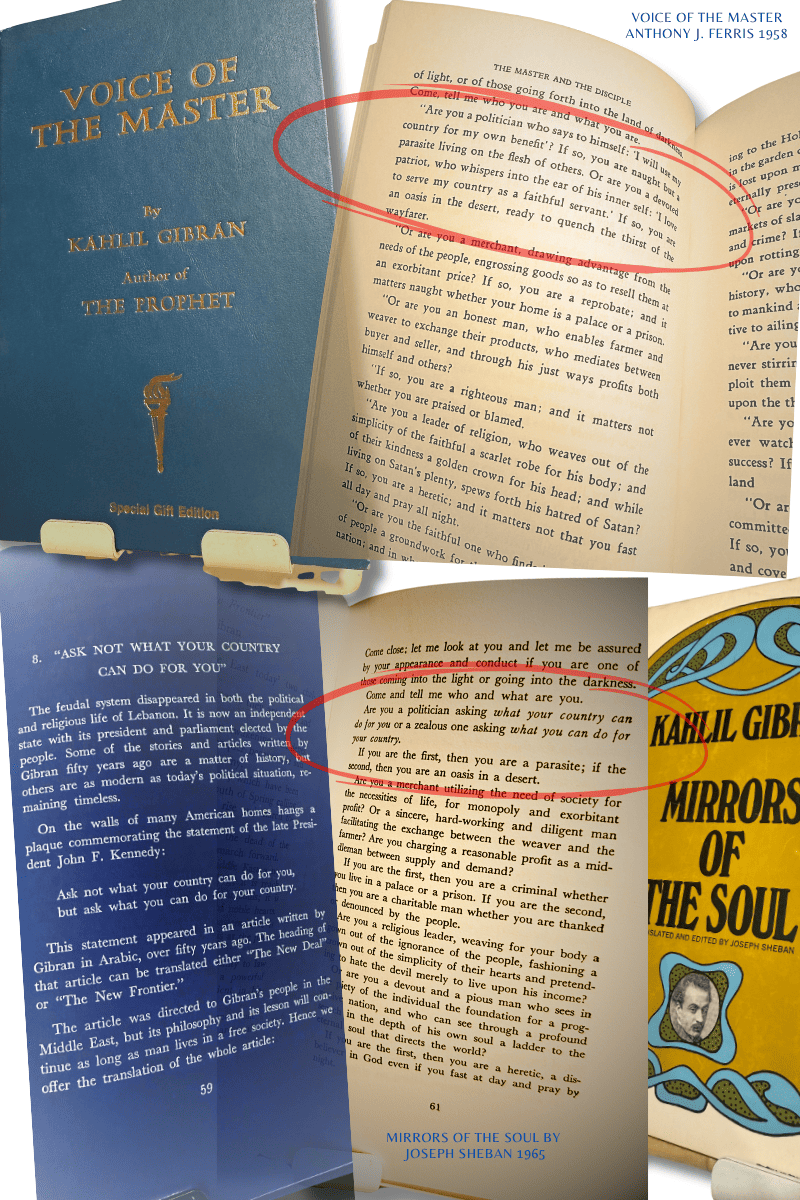

Adding another layer to this discourse, Tanis discovered—decades after the initial inquiry—that a 1958 English translation of Gibran's 1921 essay did, in fact, exist.

This translation was produced by Anthony R. Ferris, an author of several translative works by Gibran, in the 50-60's. Ferris's insertion of the said quote, unlike Sheban's dedicated chapter to the quote, was strangely published within the pages of an eclectic collection he compiled and titled Voice of the Master. Critically, this version was published without a clear citation to the original 1921 essay, rendering it obscure. There was no mention of its original title either, be it A New Era or New Dawn.

The circumstances of its publication are indeed peculiar. A few years ago, I managed to locate and speak with his son, Anthony "Curley" Ferris of Texas, to see if he had any information on the subject. Curley only recalls his father travelling to Lebanon in 1955 by boat with the entire family to study Gibran's Arabic works, and that he brought copies of the Arabic texts back to the USA. His father's sources are now in Texas and one day deserve a visit to be fully examined.

Nevertheless, the mere existence of this 1958 translation fundamentally challenges the JFK camp's chronological argument, as it proves an English version of the 1921 essay was available before the 1961 inaugural address. Whether this specific translation was accessible to Kennedy's team remains an open question. But before this discovery can be accepted as conclusive proof, a closer examination and comparison of the 1958 and 1965 translations is required.

Under the microscope, both the 1958 translation by Ferris and the 1965 by Sheban have some questionable differences. Is it a translator's artistic license? Maybe, so I have provided below a variety of translations, including the original Arabic and another word for word Arabic translation made by a colleague and Gibran Scholar and biographer, Jean-Pierre Dahdah.

ARABIC SOURCE:

Egypt 1921, the essay by Gibran The New Era was published first in the Egyptian magazine Al-Hilal on April 1, 1921. It was later published in a book entitled Al-Bada'i' wa- 't-tara'if (The Beautiful and the Rare) in Cairo (Yusuf Bustani, 1923).

Original Arabic:

أﺳﻴﺎسي ﻳﻘﻮل في سرّه : أرﻳﺪ أن أﻧﺘﻔﻊ ﻣﻦ أﻣّﺘﻲ ؟

أم ﻏﻴﻮر ﻣﺘﺤﻤّﺲ ﻳﻬﻤﺲ في ﻧﻔﺴﻪ : أﺗﻮق إلى ﻧﻔﻊ أﻣّﺘﻲ ؟

إن ﻛﻨﺖ اﻷوّل ﻓﺄﻧﺖ ﻧﺒﺘﺔ ﻃﻔﻴﻠﻴّﺔ،

وإن ﻛﻨﺖ اﻟﺜﺎﻧﻲ ﻓﺄﻧﺖ واﺣﺔ في ﺻﺤﺮاء .

Translated Arabic (literal) by Jean-Pierre Dahdah

Are you a politician who says in secret: "I want to benefit from my nation"?

Or are you a zealous enthusiastic whispering to himself: "I yearn to benefit my nation"? If you are the first, you are a parasitic plant. And if you are the second, you are an oasis in a desert.

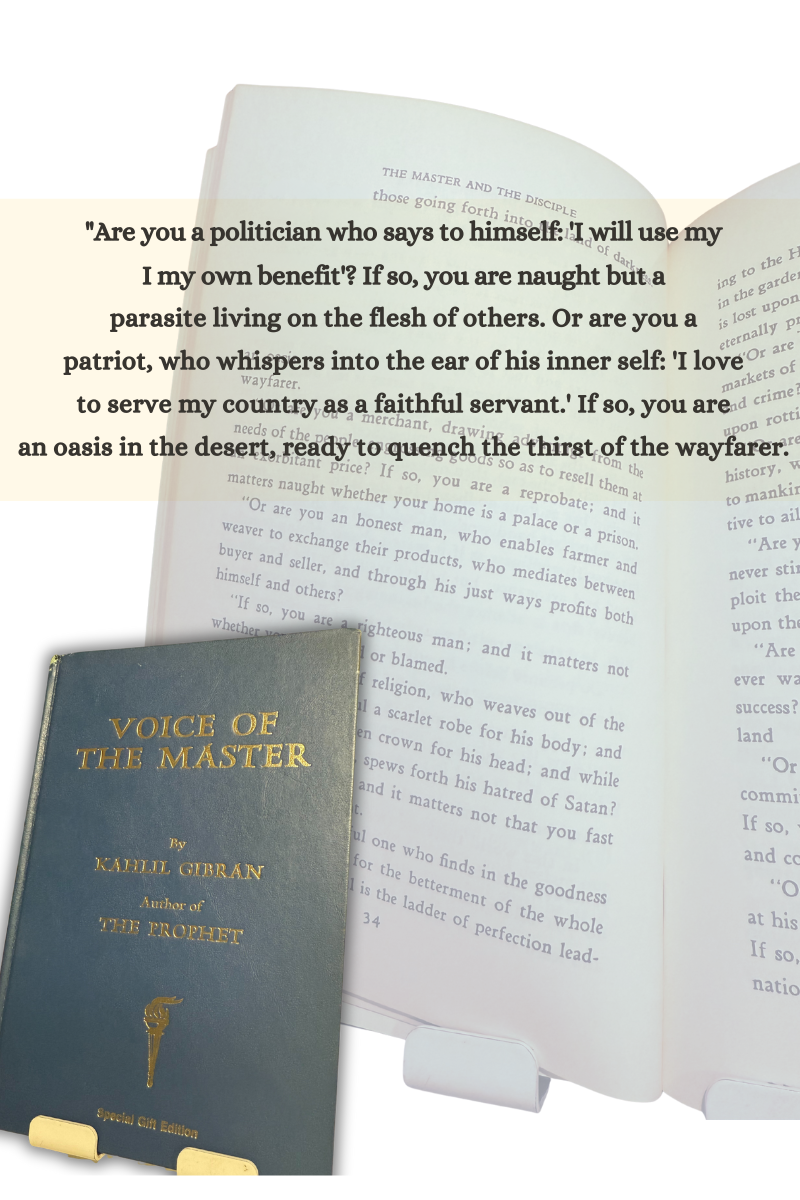

The essay's first English translation appeared in 1958, noted in chapter two under the heading of the Voice of the Master. The book was an eclectic collection of various Gibran pieces translated by Anthony Ferris. The section identified in the 1958 Ferris translation with no citation was the following:

Are you a politician who says to himself: "I will use my country for my own benefit"? If so, you are naught but a parasite living on the flesh of others. Or are you a devoted patriot, who whispers into the ear of his inner self: "I love to serve my country as a faithful servant." If so, you are an oasis in the desert, ready to quench the thirst of the wayfarer.

The 1965 book Mirrors of the Soul, translated by Joseph Sheban, included a section with the heading "A New Frontier," which reads…

"Come and tell me who and what you are. Are you a Politician asking what your country can do for you or a zealous one asking what you can do for your country. If you are the first, you are a parasite; if the second, then you are an oasis in the desert."

However, this publication had two key differences, which could be the source of the misunderstandings. Sheban titles this essay The New Frontier (matching President Kennedy's campaign theme...). The phrase in question was also translated in such a way that it matched, word for word, President Kennedy's own original crafted, Ask not...

…The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavour will light our country and all who serve it — and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

The use of titles from both translators POV is also worth a dive into.

The word 'Era' (Ferris) vs 'Frontier' (Shaben) are contextually quite different when you take in the original essay as a whole (its intentions) and Arabic linguistics in general. Gibran's original Arabic title, pronounced, al-'ahd (the era or dawn) al-jadeed (new) العهد الجديد – perhaps is best defined as "a new period of time"–or "a new ruling period over time". For example, the Old Testament in Arabic is referred to as al-'ahd al-kadeem (the old era) and the New Testament is called al-'ahd al-Jadeed (the new era).

The word 'Frontier' denotes a border or a crossing of borders. This might conjure up images of Sir Douglas Mawson reaching the southernmost geographic pole or… JFK's drive to send folks to the moon. Usually this is a heroic event, or a singular moment of independent change made by an individual or group.

The word 'Frontier' denotes a border or a crossing of borders. This might conjure up images of Sir Douglas Mawson reaching the southernmost geographic pole or… JFK's drive to send folks to the moon. Usually this is a heroic event, or a singular moment of independent change made by an individual or group.

"An 'Era' is perhaps defined by a fundamental and irreversible shift in the human condition. These shifts can be technological, like the Agricultural or Industrial Revolutions; intellectual, like the Scientific Revolution or the Enlightenment; or societal, like the rise of democracy or the abolition of slavery. Even recent developments like the Internet mark the beginning of a new, digital era, reshaping communication, knowledge, and identity on a global scale."

Both, however, symbolise great moments of change and/or accomplishment–a paradigm shift of the mind and spirit, or technological development ushering in new levels of thinking and possibilities.

As noted, Gibran's essay was composed against a backdrop of geographical and societal upheaval within his beloved homeland. Conscious of the great wave of change shifting his people's minds and the dissolution of old borders, he sought to convey the dawn of a new 'ahd—an era, a covenant, a testament. This new consciousness, he believed, would create new frontiers of the mind and establish a renewed pact for our daily lives.

In his conclusion, Tanis notes: "…this translation was manipulated to make it appear that President Kennedy plagiarized Gibran's phrase", a reasoning that the JFK camp would argue is chronological evidence against the plagiarism charge, because it was written four years after the Kennedy speech in 1961. Yet Tanis's research has uncovered, "that this is not historically correct and is a misrepresentation of the literary truth."

Although Tanis successfully disproves the connection, he also argues that the two quotes should be accepted as 'similar', as other recorded quotes in the JFK Library do. He notes:

It is now the moment when by common consent we pause to become conscious of our national life and to rejoice in it, to recall what our country has done for each of us, and to ask ourselves what we can do for the country in return. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Tanis theorises that maybe Gibran himself had read this speech from Holmes, and in a 2009 interview with Ted Sorenson, JFK's main speechwriter, he suggests that Kennedy himself may have come across Holmes’s version, perhaps via his headmaster at Choate College. Interestingly, Sorenson is dismissive of any connection and asserts it was JFK's original thought.

Without an in-depth check of both men’s notes and libraries, it is hard to tell if Gibran and Kennedy read Holmes's work. I can corroborate, although not fully assert, that JFK's favourite books do not contain any work of either Gibran or Wendell Holmes Jr, and according to the Gibran Museum of Lebanon, no copy of Holme's work exists there either.

When evaluating other historical texts or articles on this topic, it is important to approach any inconsistencies with caution. Apart from the 1965 translation mentioned earlier, it is widely understood that any mistakes were not deliberate but were made in good faith, but based on information from other sources that evolved into what can be described as intellectual rumours. Unfortunately, these were built on false premises that persisted over time. This article aims to clarify and correct these long-standing misconceptions.

Tanis writes…

My hope, as the research was unfolding, and as expressed to the Kennedy Library, is that, with this conclusive article, it cannot be said that the "Ask not..." Kennedy quote was taken from Gibran; however, the Gibran quote should be noted on the Kennedy website as a similar quote just as Oliver Wendell Holmes's is.

Indeed, in these modern times, with tensions in the world between East and West, what better way to honour the legacy of Kennedy and of Gibran than to share with the world that two great thinkers from different cultures do not clash, but coincide, sharing a common thought. It is that oneness of thinking that should be expressed as part of the healing process, and to remind us that we are one and the same, sharing the same planet, looking for harmony and honesty, not violence and vitriol. This is what President Kennedy lived and died for–to ensure that we care for one another. This is the essential message that the lives and writings of both Gibran and Kennedy have left us–to search within ourselves for genuine empathy towards one another. Let us recognise this joint heritage, acknowledging that just as there are similar teachings in religions with an underlying universal message emanating independently from different sources, so, too, in philosophy and critical analysis, there are similar concepts and wording, as already accepted on the Kennedy Library website.

This posting of Gibran's 1921 quote would be a much-needed contribution to changing the way we think, to see how we are alike, not different. The excerpt from the Gibran 1921 Arabic quote translated in 1958 by Ferris reads as follows:

Are you a politician who says to himself: "I will use my country for my own benefit"? Or are you a devoted politician, who whispers into the ear of his inner self: "I love to serve my country as a faithful servant"?1

It is worth noting that individuals proficient in both Arabic and English might offer a slightly different literal translation of the original 1921 Arabic essay by Gibran than the one provided above. However, for historical and literary accuracy, it is essential to retain the quote as it appears in the 1958 Ferris translation. This preserves the integrity of the research and the published chronology.

The Originality of the Famous "Ask Not..." Quote from President Kennedy's Inaugural Address in the USA by Ernest G. Tannis Published in 2012 'The Enduring Legacy of Kahlil Gibran' Papers delivered at the Second International Conference on Kahlil Gibran: "Reading Gibran in an Age of Globalization and Conflict" October 18, 1978 New York Times interview by Bob Levey with Robert Hill Murray - JFK's Famous Phrases Rooted in History.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1978/10/19/jfks-famous-phrases-rooted-in-history/e79edc41-a153-41ec-aeb9-d94f761aec44/

In 1921, Al Halil Newspaper العهد الجديد The New Era in Arabic.

Kahlil Gibran Collective Archives

Secrets of The Heart by Anthony J. Ferris 1958

https://www.philosophicallibrary.com/authors/kahlil-gibran/

Mirrors of The Soul by Joseph Sheban 1965

https://www.philosophicallibrary.com/authors/kahlil-gibran/

Image

Image * JFK's Handwritten Quote: "Ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country"

https://www.shapell.org/manuscript/jfk-handwritten-quote-ask-not/

Image *JFK 1960 SLOGAN BUTTON

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_F._Kennedy_1960_Campaign_Button_%28background_removed%29.png